Ideas

Zine Review: Dead Planet Cookbook

Artist Pallavi Sen began the Dead Planet Cookbook (2018) by quoting Indian scholar and environmental activist Vandana Shiva: “Eating is an ecological act! Eating is an ethical act! Eating is a political act!” and dedicated the zine’s following 100-odd pages into reflecting on the essence of these three short sentences.

I found the zine on the Brooklyn-based printing initiative GenderFail’s web platform. Printed using Risograph, in black and burgundy, I longed for its tactility. With certain pages coming out lighter than others, some paragraphs became whispers that required multiple, close readings to grasp. Such variation in ink density is common with the Risograph, for the machine takes time to learn each page’s pattern. As I read, the ability to zoom in quickly offset my perceived initial drawback of the soft copy.

The Cookbook arose out of Sen’s aim to only eat food prepared at home, to buy in bulk, to follow the seasonality of produce, and to avoid buying ingredients wrapped in plastic. These objectives were motivated by her 2016 residency at the Wormfarm Institute, Wisconsin, where the residents were encouraged to eat what they harvested. In her introduction, she recounts her reflections on sustainability and art-making during the residency:

“Here I am brushing acrylic paint onto something made of wood. It will look so good when documented, maybe I will be selected for something like a grant or residency, I would have made professional progress . . . But in my lifetime, and beyond it, my sculpture will only devastate the soil and water, poison animals and plants.”

Her movement toward home-cooked meals and her incorporation of cooking in her practice came at this juncture; a pivot driven by a self-awareness of how art practices sometimes, ironically, contribute to the devastation of the environment that they proclaim to champion, or at the very least, pretend to care about. Indeed, are all artworks truly worth the resources they use? In a world full of things, isn’t a sustainable art practice one that pauses, or minimizes, the production of new objects?

Cooking and community kitchens have gained traction recently as art practices, perhaps due to food’s very materiality. Edible materials are biodegradable; they are consumed by both human and nonhuman players in the ecosystem, and in turn, do not occupy our finite available space for too long. Food nurtures in the most visceral way, in addition to the intellectual nourishment artistic production intends to achieve. Food is also accessible: everyone eats.

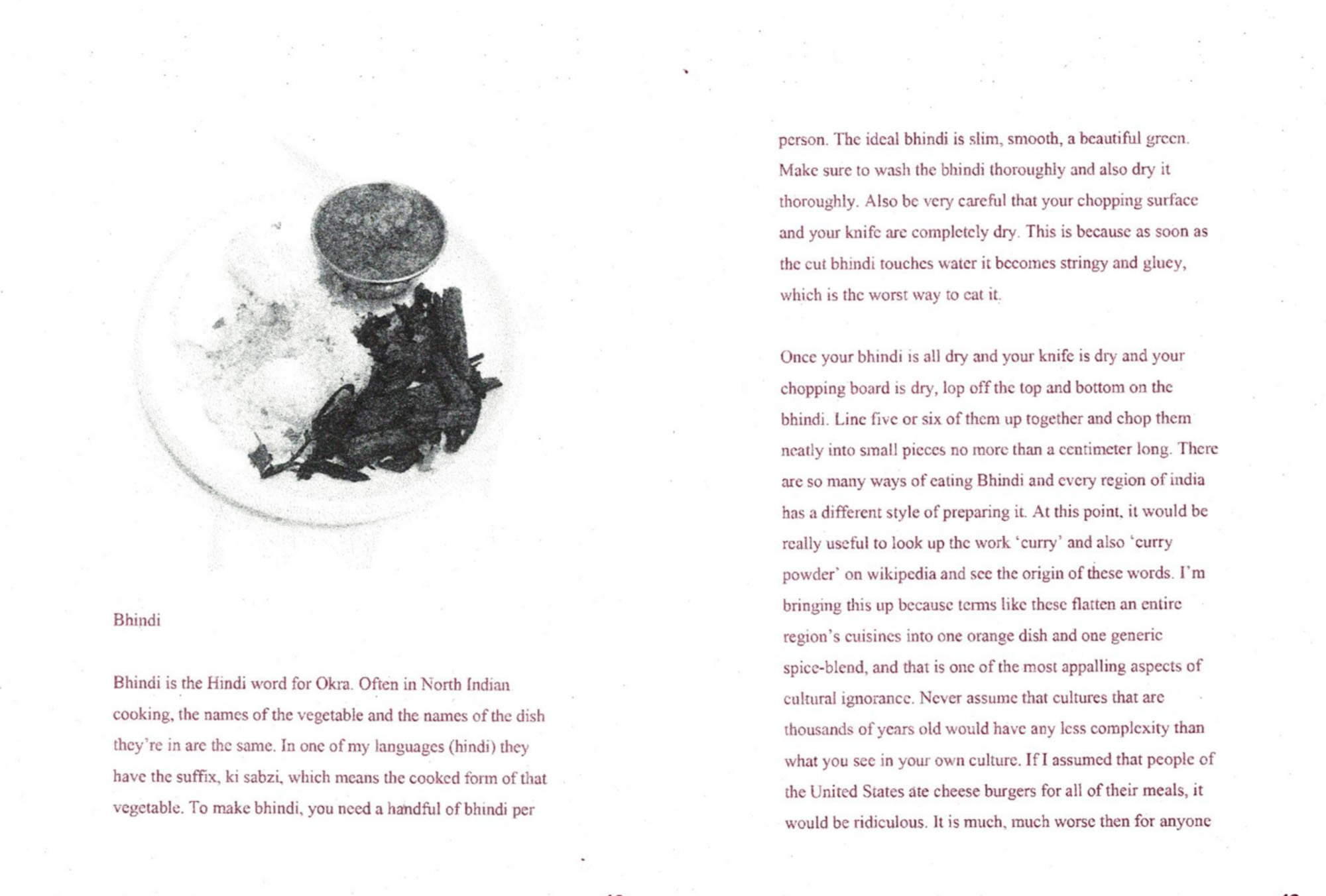

Sen underlines access in her recipes, the zine’s body. The recipes are for dishes that use “a standard set of spices. . . found in North Indian homes, like the kind [she] grew up in,” from Arhar Daal (Split Pigeon Peas) to Bhindi (Okra), and are designed to reduce the usage of plastic while being affordable.

These recipes do not come in lists of ingredients with step-by-step, numbered instructions of preparation, instead Sen writes them in paragraphs as though she and the reader are having a conversation. Incorporated here are the meaning behind names of dishes and how to correctly pronounce them (Arhar Daal is “ur-hur daal”); the specificities of Indian pressure cookers, which whistle when the food is ready; detailed explanations on the arbitrary systems of measurement that arise between different communities (how much is “just a little”?); and the acknowledgement that the dishes will become better the more you cook them.

In the section on rice, Sen laments on how she misses eating roti alongside rice with her meals since her switch to home-cooked food. A laborious undertaking to make, “one could eat fresh rotis in India because of the availability of domestic help who rolls the roti out while the family eats without them or a mother who eats afterwards.” Cooking as a labor often managed by certain individuals in a household, as opposed to a task that is shared evenly, is a distinction that is most visible in complex dishes. As Sen suggests, we also “need to rethink how hot foods can be served in a household of equals, where one person acts as preparator as another eats.” Thinking more deeply, this conversation is a microcosm of how labor in global systems of food production is distributed, with a majority of the world’s population being fed by individuals in developing countries who are prone to exploitation. Often it is the people who feed us who do not get a seat at the table.

The Cookbook ends with a manifesto. Numbered and capitalized, it outlines methods of how to live a more “anti packaging, anti food waste, pro clean plate, [and] pro small budget” way of life by eating at home. In Hong Kong where I am based, preparing all of your meals at home is often more expensive than buying take-out or pre-packed instant dishes, especially for those living alone. In the zine, Sen recognizes how particularly difficult it is to create such alterations to one’s lifestyle in urban spaces. While it may not be economically feasible for everyone to make such adjustments, for those who it is, this zine provides a few good recipes to begin with.

It is very easy to turn to despair that our small acts of care will not make a dent in preserving our environment and in improving the lives of those who grow and prepare our food as long as corporations stand to profit. But what we put in our bodies to fuel it is a decision we can control. Eating can be resistance. In Sen’s Cookbook, I found new ways of feeding myself. Maybe I will make Arhar Daal, using as little plastic as possible, while sharing with as many people as I can. Gone are the days of the starving artist. In a time of urgency like ours, the artist must be nourishing, even if it means reconsidering methods of production, even if it means brawling for a place at the table.

“Zine Review” is a column by ArtAsiaPacific’s assistant editor Nicole M. Nepomuceno, where she reports on independent print matter.