Ideas

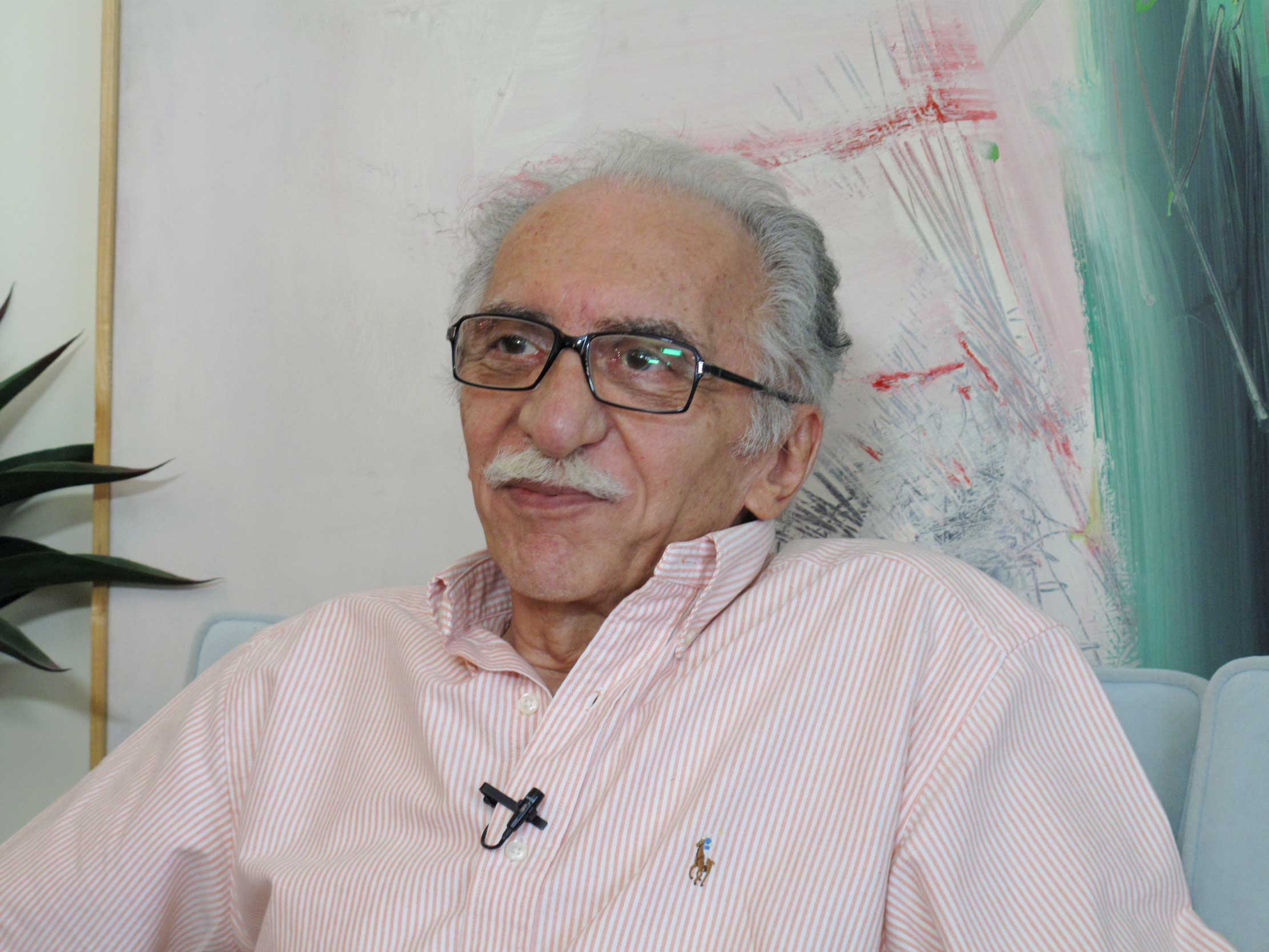

Traces of Time: Interview with Zhang Yu

Born in Tianjin in 1959, Zhang Yu is among the pioneers of contemporary Chinese ink art. He began his career in traditional Chinese painting during the earliest years of China’s reform period, eventually departing from the rigid rules of ink and brush, and testing the boundaries of the genre. Moving beyond works on paper, he later started developing performance-installations that incorporated his body and time-based change. For instance, at his recent Tea Feeding performance at Art Basel Hong Kong, he poured tea into 30 cups, allowing the beverage to overflow and leave flowering patterns on the xuan paper beneath. On the occasion of his first solo exhibition in Hong Kong, at Alisan Fine Arts, Zhang spoke with ArtAsiaPacific about the post-Cultural Revolution development of ink art, his interpretations of the genre, and how art should reflect human nature.

How did you become exposed to art?

I spent eight years in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution, doing all kinds of farmwork. Many artists and intellectuals—including Ma Da, the president of the Tianjin Artist Association—were also sent to the countryside as part of their “re-education.” Fortunately I met Ma there in the 1970s, and learned to draw from him. He was most interested in sculpture and woodcut printing, as well as seal carving, so I learned those too. After the Cultural Revolution, when I returned to the city, I joined Yang Liu Qing Painting Society and took charge of the engraving and carving process for their nianhua [colored Chinese woodblock prints commonly used for New Year decorations], which is very close to traditional gongbi paintings. I also did oil painting in my leisure time, but when my boss saw it, he forbade me from doing it because it was “Western.” I then turned to traditional ink painting. Later, when I became an editor and layout designer for the Society, I was exposed to different kinds of publications, and began to publish on Chinese paintings.

Since the 1980s, you have published several books on traditional Chinese painting and modern ink art. How did you engage with these genres?

When we talk about contemporary Chinese art history, we always think of the ’85 New Wave, when there was an influx of Western thought, culture, and art in society. Young people were so shocked by this exposure to the unknown, outside world that they started to learn and imitate it. We started to develop an awareness of the need to modernize our own art. I was interested in traditional Chinese painting, so I established a magazine, The World of Chinese Painting, to promote the modernization of the genre.

Modern ink painting became a trend in mainland China under the combined influence of Taiwan and Hong Kong’s New Ink movement which took off in the 1980s, and drew inspiration from elements of modern Western art. By 1991, when I was finally able to publish the book series Chinese Modern Ink Paintings, I had moved away from the idea of traditional Chinese painting and started conceptualizing the genre of modern ink painting. While working on another book series, The Artistic Trend of Modern Chinese Ink and Wash in the Late 20th Century (1993–2000), I got rid of the term “painting” altogether. I intended to remove the presumption of modern ink painting as “the combination of East and West,” and consider ink as a unique medium, not just a vehicle to portray Western realism, expressionism, or abstraction.

What inspired you to write your article “Declaration of Experimental Ink” (2000), published in the book series The Artistic Trend of Modern Chinese Ink and Wash in the Late 20th Century?

When we choose ink as our point of departure, we depart from the traditional brush and its rules. This is only possible when we [stop] focusing primarily on the relationship between ink and painting. In 1993, [curator and art historian] Huang Zhuan proposed the idea of “experimental ink painting” in the magazine Guangdong Artists, which I found problematic because it was still stuck within modern ink painting. So in 1995, when a Hunan magazine invited me to edit an issue, I themed it around the genre of “experimental ink”—focusing on water and ink—which does not only refer to abstract ink paintings, as conceived by many Chinese critics. Some might say it’s “non-figurative,” but it is still different from the Western idea of abstraction. It expresses through graphics, as in my Divine Light series (1994–2004). The Declaration clarified my understanding of and intention with experimental ink.

How do you view the relationship between tradition and contemporaneity?

There is a premise for advocating a departure from tradition and rules, which in this case is the historic Chinese obsession with brush and ink. What is “brush and ink?” We have always valued brush and ink but never questioned if it has independent values. Traditional Chinese paintings are figurative, based on yingwu xiangxing [one of the six rules], meaning “proper representation and fidelity to an object,” similar to Plato’s idea of imitation. Each brushstroke, then, is tied to the essential structure of the painting and it is impossible to extract the brush. All the modern ink masters, including Huang Binhong, Xu Beihong and Lin Fengmian, didn’t succeed in establishing independent values for brush and ink, except for the Japanese artist Yuichi Inoue who, based on the style of the calligrapher Yan Zhenqing, turned each stroke into a form of abstract expression, which happened to coincide with American abstraction in the ’50s.

Our “roots” are connected with the form of our visual languages. It is possible to move forward only when we deconstruct brush and the ink. Experimental ink breaks away from traditions through its methods of its creation as an expression of our being. For example, for Divine Light, I sprayed and painted with water before repeatedly rubbing the paper. Although it seems to embody a similar ambience as traditional Chinese paintings, you can also interpret it as a representation of the cosmos. This is where its contemporaneity comes in. In a way it surpasses reality, instead of simply imitating it.

For your large-scale 2016 installation Shang Shui (Water Feeding), over six days, you filled 10,000 bowls in Youguo Temple, Mount Wutai, in Shanxi Province. Could you talk about your inspiration for this project?

It is a pity that the Chinese titles in this series are difficult to accurately translate. The character shang (上) [up] means more than “feeding”; it also hints at my process of painting, the vaporization of water, the act of pouring and serving these “drinks.” This project is an extension of my Fingerprints series (1991– ), where I started pressing fingerprints using tea and water. They are both acts of shangcha (filling tea) and shangshui (filling water), and follow the same logic of removing the term “painting.” They are both performances and installations, but also works on canvas. They have multiple forms, a complete status. The results are surprising but less significant to me since I express all of my thoughts during the process.

For Ink Feeding (2005– ), I placed emphasis on my body and the act of pouring the ink. As I poured it into bowls or acrylic boxes, I allowed the ink to gradually settle into and become diluted on the xuan paper. With this, I returned to the basic elements of water, ink, xuan paper, and the gallery space. The ink interacted with the space and its climate through time, although we couldn’t actually see its vaporization and transformation while it occurred. In a way, I let the work grow, like planting seeds and waiting for harvest. The artwork becomes alive, making it unique. It made me reconsider shanshui paintings: they look mechanical compared to [Ink Feeding]. Manual acts of imitating nature cannot produce something as lively as art that grows organically.

Tea Feeding (1992– ) is different [from Ink Feeding] as it is an act originating from daily life. We pour and serve tea as an etiquette. I turned this act into an artistic expression with the passage of time. The results are more fruitful than Ink Feeding; there’s another layer added into the process of creation. For Ink, there were three layers: the interaction with the space, the performance, and the effects on xuan paper. For Tea Feeding, the bowl is also added to the process.

You’ve discussed the idea of “existential art” and “awareness art”—could you unpack these?

Western art history emphasizes symbols. This kind of art is removed from the public. It is only when art brings in the collective consciousness that the public can understand it. Thus it is necessary for us to depart from merely forms and symbols. My acts of pressing the fingerprints onto the canvas come from my motivation to perceive reality and understand our existence. What I’m looking for is not the result or the form that comes out of my works, but the constant process of perception and expression. “Form” is not the foundation of art—humans are. Only when you explore humanity in art can you establish your own existence and value of being. I hope that when people see my work, they see what kind of person I am, what I create, and where I stand on issues of art history and society.

Pamela Wong is ArtAsiaPacific’s assistant editor.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.