Ideas

The Neon Glow of Clichés

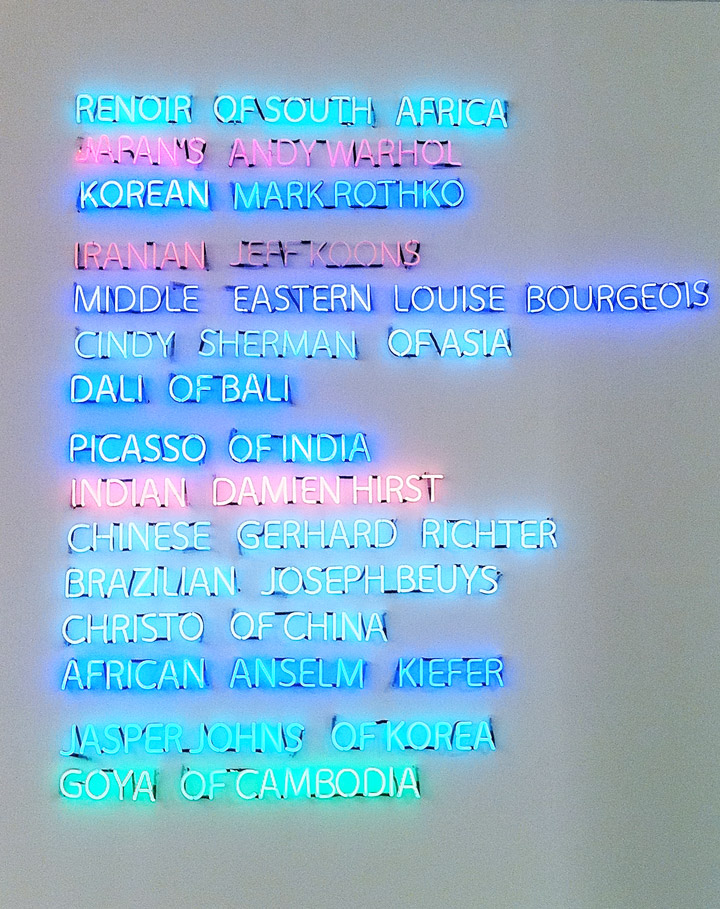

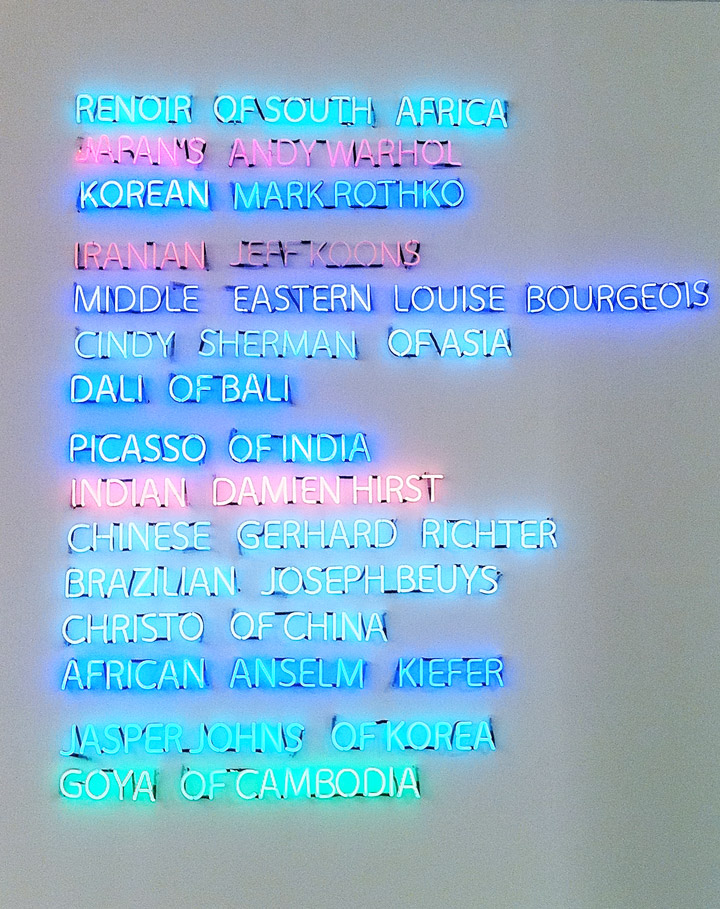

Wandering around the halls of Art Dubai two weeks ago, I found a work that spoke to me as a long-suffering editor. Hanging on the outer wall of Christian Hosp Gallery’s booth, the neon tubes of Leila Pazooki’s Moments of Glory (2010) flickered with rich, multicolor satire, parading an embarrassing series of transnational clichés.

Japan’s Andy Warhol. The Iranian Jeff Koons. The Picasso of India. The Indian Damien Hirst. The Jasper Johns of Korea. “I know who these people are!” I thought to myself in a moment of self-congratulatory point-scoring. Do I want to name them here? No. Because these are the glib monikers given to artists from regions outside the United States and Europe by writers and editors who are too lazy to consider these artists’ work on its own terms, and I wouldn’t want to perpetuate the associations further. While there may be valid connections or parallels between these artists and their alleged Western counterparts, those who pay serious attention to these complicated art-historical issues are unlikely to employ such reductive terms.

Do I know who the Cindy Sherman of Asia is? Not sure. It brings to mind a Japanese artist and a Korean artist. So does the term refer to both of them? Oh wait, the Japanese artist is male, so it must be the Korean artist. Too bad, the process of elimination pinned us both down. For a moment there, I was wondering if there was a third person I wasn’t aware of: a chimeric pan-Asian artist with the blood of 1,000 ethnic groups running through his or her veins, producing photographs dedicated entirely to emulating Cindy Sherman’s career. If only! Sounds like a scoop!

Meanwhile, around the corner, the ArtAsiaPacific booth was laden with copies of issue 72, which features Wafaa Bilal on the cover. Earlier in the day I had asked a fellow member of the press if he knew about Bilal, an artist and New York University professor who recently caused a media frenzy when he had a small camera surgically implanted on the back of his head, where it takes a picture every minute. “Oh yeah! You mean Dr Camerahead?” the journalist said. I hesitated in a moment of genuine shock. Fine, I had already seen this moniker appear in the press, but having just spent several months interviewing Bilal in depth about his practice—which in large part originates from the trauma of his exile from Iraq in 1991 and the deaths of his brother and father following the 2003 invasion—it was jarring to hear his life and the 3,500 words I wrote summarized in two.

But then I suppose two words are easier to tweet. Easier to retweet. Easier to follow. So perhaps that’s it, we should all embrace these monikers and agree on a standardized set of analogies for artists. Francis Bacon can be the Zheng Fangzhi of Britain and Marcel Duchamp can be the Ai Weiwei of France. We can all agree that Louise Bourgeois is the Monir Farmanfarmaian of Paris and Damien Hirst is the Peng Yu & Sun Yuan of London. If we think of Félix González-Torres as the Inhwan Oh of Cuban-Americans, then Lorna Simpson is surely the Vernon Ah Kee of the United States. Let’s call Candida Höfer the Dayanita Singh of Germany, Jenny Holzer the Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries of the US and Carl Andre the Gu Dexin of America.

Doesn’t that make them all so much easier to understand?