Ideas

The Many Faces of Antony Gormley’s Asian Field

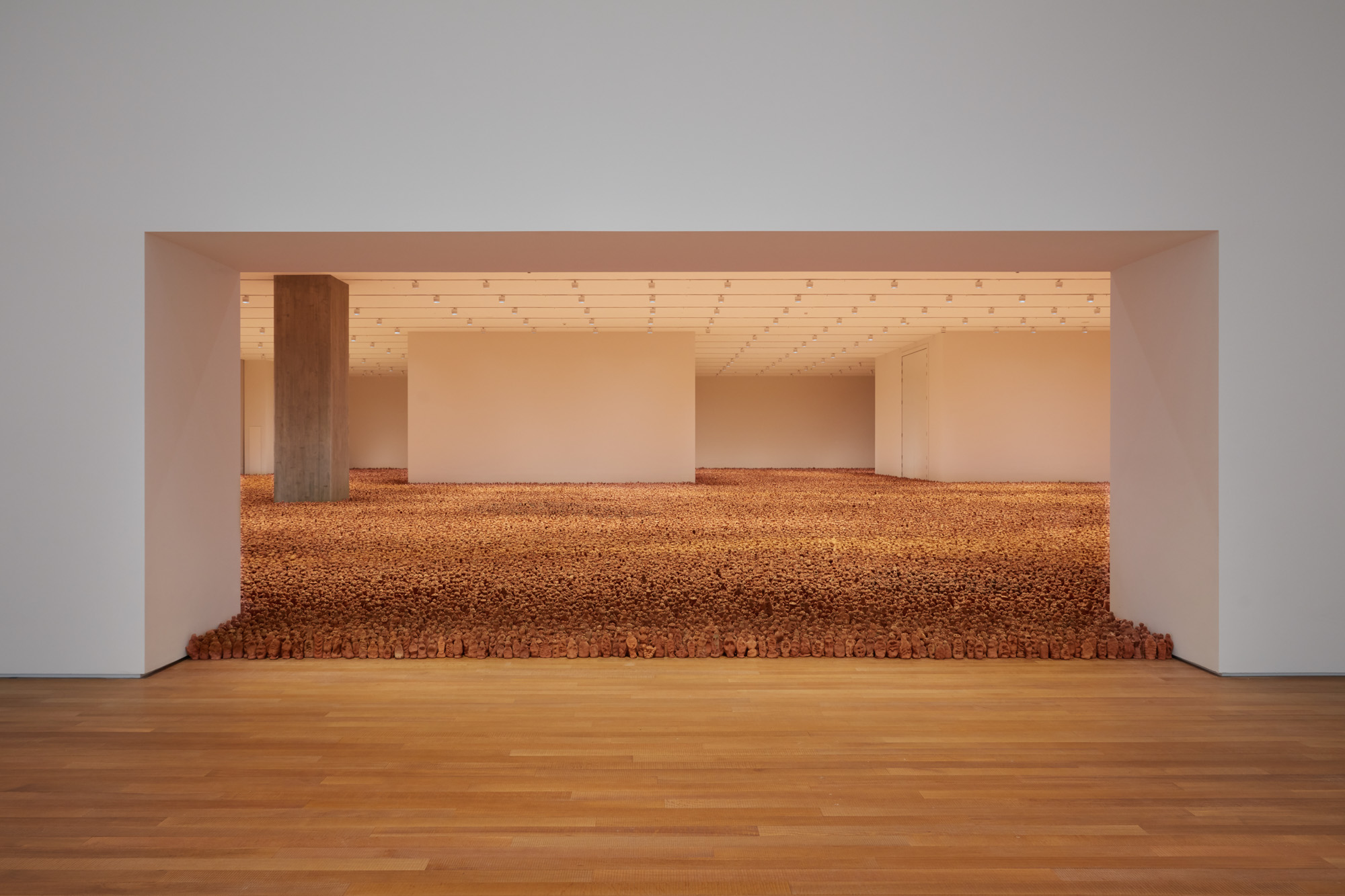

Collaborative or exploitative? Humanizing or dehumanizing? Meditative or menacing? These were questions sparked by Antony Gormley’s massive installation of nearly 80,000 tiny clay figurines, Asian Field (2003), one of the inaugural displays at M+. There, in the museum’s newly opened West Gallery, you could make out some of the figures’ individual faces, the mass of ocular indents on rounded forms gazing upward—are you one of them, or are you looking down on them? But beyond the first few meters, they merged into a landscape of rusty reds and terracotta hues stretching out to the furthest wall dozens of meters away. You started to think: Who made all of these sculptures? How did they get here? Why are they all staring at me?

Asian Field was originally created in Xiangshan Village in Huadu District, Guangzhou. Working with the British Council and through the coordination efforts of Zhang Wei from Guangzhou-based Vitamin Creative Space, between January 18 to 22, the British sculptor instructed more than 350 local residents of a then-rural area in Guangdong to press hand-sized balls of iron-rich red clay into anthropomorphic forms that could stand up on their own, with a pair of eyes for a face. Photographs from the time show people sitting in rows on an outdoor basketball court with their figures arranged in front of them. Giving only basic instructions and encouraging improvisation, Gormley wanted the process to unlock the individual creators’ emotions, and for the event to be a “collective act of generation, a democratic process that happens when you bring people together.” At the end of the five days, a local brick factory fired the roughly 200,000 figurines before they were exhibited in the parking garage of a Guangzhou housing complex from March 23 through June 15, and subsequently toured to the National Museum of China in Beijing, a Shanghai warehouse, and a supermarket in Chongqing.

Asian Field was the penultimate in the series of six “Field” installations that the British sculptor began in 1991 with brick-makers in the parish of San Matias in Cholula, Mexico. He writes about the series: “I wanted to work with people and to make a work about our collective future and our responsibility for it. I wanted the art to look back at us, its makers (and later viewers), as if we were responsible—responsible for the world that it [Field] and we were in.” The artist also shared that he feels the iteration of the installation at M+, “gives voice to the voiceless and materializes a feeling of our present predicament in a time of migration, protest, overpopulation, and climate emergency.” According to M+’s lead curator of visual art, Pauline J. Yao, the museum chose to feature Asian Field in its inaugural displays, “because of the values it upholds . . . it is in fact a work of collaboration . . . a way of reminding us that anyone can be an artist, and that we all have creativity inside us.”

The way we see art changes with time, as do the values the work projects. Despite Gormley’s humanistic aspirations for the work to represent these questions of our shared humanity and a sense of communality, when we look at Asian Field today, it can be hard not to see it through a more critical lens. It is an embodiment of labor that wasn’t the artist’s, of the power dynamic between a White, foreign artist with sponsorship from the cultural wing of the British Government—a former colonial empire that had not too long ago exerted its power in the region—and the comparatively resource-poor residents who created the work. Asian Field was also made at a time when the Pearl River Delta region was developing at a dizzying pace; as such, it’s hard not to think about its parallel relationship with “outsourcing” and the free-market experiment of the Guangdong region, which emerged as the world’s manufacturing center in the 1980s and ’90s.

Yet, from the project’s inception, Gormley went to significant lengths to acknowledge those whose hands had actually created the figures. As with all the iterations of Asian Field, at M+, the names of the volunteers appeared on a wall. A separate gallery featured photographer Zhang Hai’er’s closely cropped black-and-white photographic portraits of the volunteers next to a sample of their creations, a series he calls Makers & Made (2003). A video outside the gallery even featured interviews with participants, at least one of whom was inspired to become an artist herself. Another key component is the response board, where people could write their thoughts after viewing the work. Gormley reflects in an interview with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist from 2017 that in its first year on tour in China there was a large range of reactions to it, from people seeing it as “alien” to it evoking their recollections of military conscription, the state’s one-child policy, or, in the artist’s words, as an expression of “the feelings of alienation through indoctrination.”

The sense of the artwork as representing “values” was first articulated in a contemporaneous account by writer Hu Fang, who was involved with the project as a cofounder of Vitamin Creative Space. As Hu observes Asian Field’s Beijing display at the National Museum of China in Tiananmen Square—where after its journey “thousand miles from south to north, it immediately became part of the history of a nation”—he writes: “Asian Field suddenly seems to have stirred up a powerful collective consciousness. This space seems to convey and represent a search for some kind of lost values. Face to face with the clay figures, people realize that such values actually still exist, that they are always in people’s hearts.”

These questions about the dynamics of representation—who gets to represent whom and whose humanity being is portrayed by whom—muddy the more generous readings of the work as a collaboration or a representation of a shared humanity. The title arouses a certain discomfort for many in the present moment. What exactly is “Asian” about the artwork, or the artist’s own cultural orientation? Was the work’s creation also meant to represent the people of Vietnam, the Philippines, or Japan—or does China somehow represent all of “Asia”? For the artist, perhaps it did. As he recounted to Obrist about arriving in Beijing from Japan (no less) in 1995: “Suddenly, I felt I am in Asia. Something about the smell, the way that people were happy to touch each other . . . there was this jostling crowd of very lively people, shouting; the whole level of sensory experience went up.” Does the “Asia” of Asian Field represent the artist’s sense of difference, of the encounter with the un-individuated mass of the Other, in that classic trope of orientalism?

Perhaps the historical subjects of colonialism and orientalism are not ones that M+ is ready, or willing, to tackle. And yet the museum, focused on the visual cultures of Asia, is physically located in a former British colony (regardless of what Hong Kong’s new textbooks are now saying), and is meant to be a repository of cultural artifacts and the memories, and values, they embody. Some of the more generous assumptions about art’s active role in society are harder to summon given today’s context. You are reminded on the way into M+: the West Kowloon Cultural District has planted the international auction house Phillips right outside the museum’s entrance to seamlessly bridge cultural productions with their private ownership and financialization, and where works by Gormley and Yayoi Kusama and countless others will be sold in relation to the museum’s prestige and the cultural value it confers on certain artists.

This very contemporary marriage between the museum and global capital helps us to realize that the humanist values represented by Gormley’s work—however we parse or contextualize them—are indeed antiquated, and even historical. Hu Fang’s response at the time of seeing Asian Field was that he could only express his emotions through questions such as: “What is the relationship between words and emotion? / Is there a limit to emotion?/ Is it true that without these small clay figures we cannot feel anything?” But perhaps the ultimate awareness that Gormley’s Asian Field induces in us today is a profound sense of distance from a time when the phenomenon of contemporary art was a novel cultural eruption with the capability of inspiring confusion, wonder, and awe, rather than something that needs to perform critique or otherwise risks eliciting cynicism. We can see Asian Field as something that was possible only in this brief window of time as the region’s physical landscape was in transition and so too were the societal dynamics and cultural politics of the moment that allowed for it.

Antony Gormley’s Asian Field was on view at M+, Hong Kong, from November 12, 2021, to July 3, 2022.

HG Masters is ArtAsiaPacific’s deputy editor and deputy publisher.