Ideas

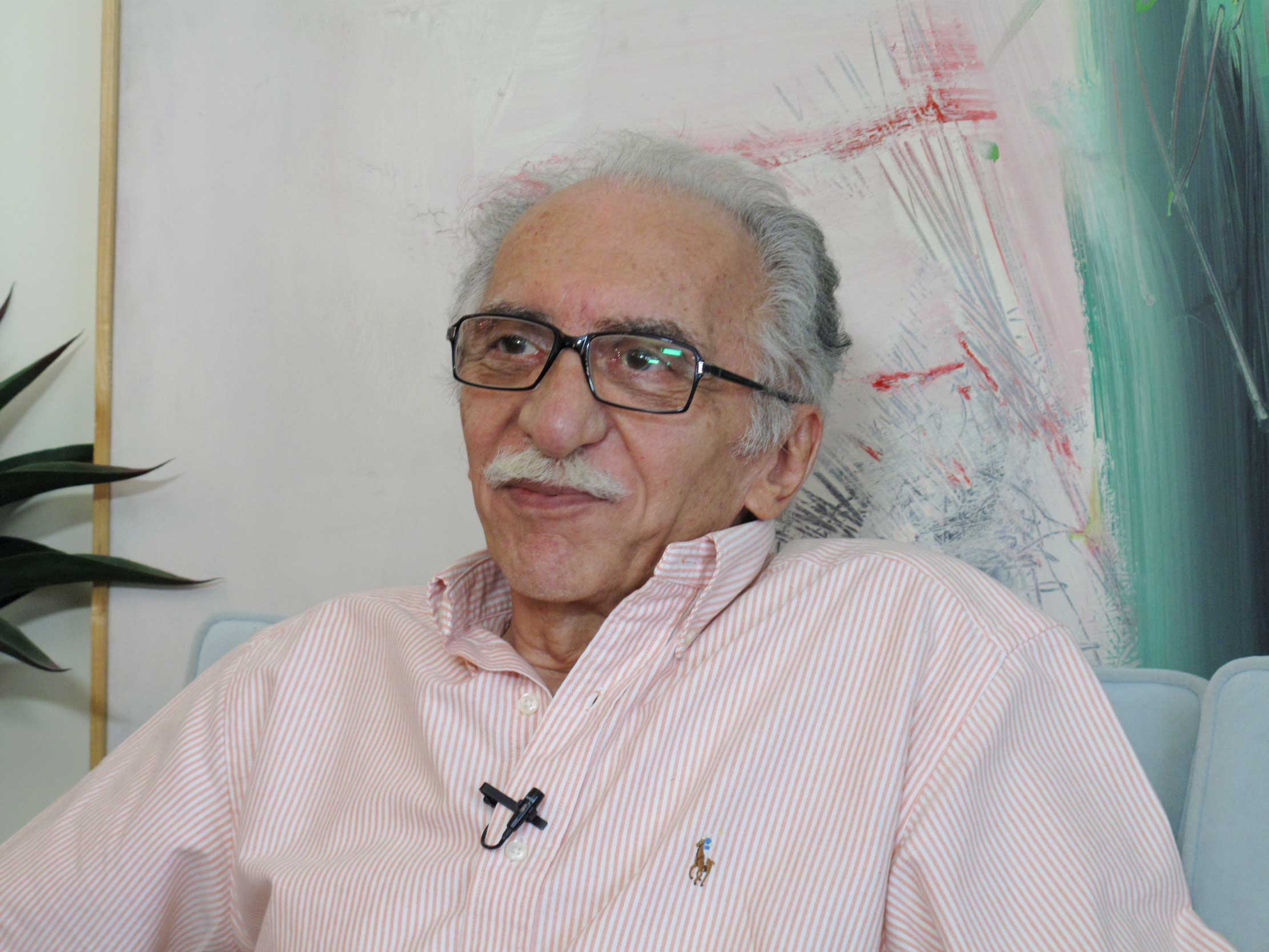

The Arrival of Tai Kwun: Interview with Tobias Berger

Tobias Berger has a proclivity for creative spaces that probe various institutional models, within which he can be a conductor of experimental ideas. Since moving to the Asia-Pacific from Europe in 2003, he has held positions at the non-commercial and non-collecting Auckland Artspace, Hong Kong’s Para Site, Nam June Paik Art Center in Seoul and the M+ Museum in Hong Kong. Perhaps most notable in his 15 years of working in the region is his consistent determination to challenge staid methods of thinking about art, expanding our imaginations as to what art can be. In 2015, he joined the contemporary arts arm of Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun—a revitalization project that has converted the colonial remnants of a former police station, a prison and the city’s central magistracy into a contemporary labyrinth for heritage and arts; a previously restricted space that will finally be open to the public. In his role as head of arts, Berger aims to not only increase the visibility of underrepresented local artists, but also to cultivate a cultural scene that is collaborative and, most importantly, inclusive. On the eve of the opening of Tai Kwun, I spoke with Berger about his curatorial strategies, the art hub’s upcoming contemporary art exhibitions and programs, and his vision for the new arts complex.

You first moved to the Asia-Pacific in 2003. How has the institutional field of arts in the region evolved since then?

I think one has to differentiate between the non-profit, alternative and independent spaces, and the commercial places, which are also institutional. In 2003, most of what happened in Asia, perhaps excluding Japan, happened within smaller non-profit institutions. It might have been the climate, but one of the most important parts of the art scene’s development was Hou Hanru’s Gwangju Biennale, titled “PAUSE” in 2002, where he brought all these non-profit institutions together. After that, these non-profit spaces became more professionalized, and more museums were built—starting in Korea, and most recently in China.

It is clear that Chinese museums do not take on the Western model of museums. They are often either connected to real estate projects or to private collections, and are forced into the commercial market. Happening almost parallel to this was the commercial boom, beginning with Art Basel in Hong Kong, which opened in 2013. Now, Hong Kong and Shanghai are two of the most important commercial art centers in the region.

You have extensive experience in various types and scales of art institutions around the world. How do you feel your role as curator has shifted? What new challenges do you face in the multifaceted art and heritage compound of Tai Kwun, compared to your work at large-scale institutions such as Hong Kong's M+ Museum, the Nam June Paik Art Center, which focuses its mission on preserving the legacy of a single artist, and smaller artist-run nonprofit spaces such as Para Site?

These institutions that you mentioned had these very old challenges, and when I joined their team, they were all start-ups or looking for a change. Nam June Paik Art Center had just opened when I joined in 2009, Para Site was looking to change its model from an artist-run space to becoming a curator-led institution, and at M+, the team was just two people. It was the same with Tai Kwun Contemporary, which I joined in 2015 when it basically didn’t exist.

Maybe this experience is something that is common across Asia—most of the institutions are not older than five years. The museums in Korea and China are all quite young, and many of the galleries are newly founded. Excluding Japan, what’s happened and still happening is basically a giant start-up phase in the Asian art sphere, and that’s what makes it so interesting at the moment! The spaces are re-inventing themselves through trial and error—some institutions find new ways of doing things, and sometimes that is interesting. Sometimes when things don’t work out, they revert back to an older model.

My role is like this history I just described. In the beginning, it was important for me to bring exhibitions, to bring local artists, to develop local artists, to move things forward, but more and more, the role becomes to establish meaningful organizations and institutions, giving them some kind of sustainable framework, be it financially, be it in terms of its governmental structure, and so on. This is a challenge but also an important part of cultivating the art infrastructure.

Tai Kwun is one of the most significant revitalization projects in Hong Kong, comprising a 1840's compound of a former Central Police Station, the Central Magistracy and the Victoria Prison. It does not simply repurpose the original architecture but adds to the fabric of the existing buildings with new structures designed and built from scratch. How do these new additions, such as the JC Contemporary galleries and the JC Cube auditorium, designed by the Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron—who are also heading the design for the M+ Museum, and built the Bird's Nest Stadium in Beijing in 2008—add to, and reflect on, Tai Kwun's role and function as an evolving site of visual culture for Hong Kong?

Herzog & de Meuron have tried to bring together the heritage and the contemporary, but we do not merge the two. We are not an institution that does exhibitions only under the eye of heritage or the contemporary. Tai Kwun has a heritage team, a contemporary art team and a performance art team because these are very different things, and they each look at how to make an exhibition in very different ways.

We have incredible gallery spaces, some of which are much more industrial with concrete ceilings, and others which are very old-fashioned with wooden floors. This is wonderful because different art and different installations do require different kinds of exhibition spaces, and this is the beauty of Tai Kwun. You walk through the whole compound—it’s big, it’s like an Italian village—and every corner you turn, you have a new attraction.

Tai Kwun is a kunsthalle that does not have a permanent collection. Does this make things more challenging or flexible when curating exhibitions?

Not having a collection speeds you up a little bit. If you have a collection, like M+, you have to work with and look back at the collection to re-evaluate it. At Tai Kwun, I think we have the chance to be a little more experimental than the larger institutions. We have room to take more chances on working with younger and mid-career artists to produce different types of works. For example, if you compare Whitechapel and Serpentine in London to the Tate Modern, they can do very different things within the art ecosystem, and it’s the same with the New York’s New Museum, which is a very different institution to the Museum of Modern Art PS1.

We are not an institution for retrospectives or survey shows, and we are not looking for artists who have already had a lot of museum and gallery exposure. We are a place where people can take chances, try out new things that make sense in the context of Hong Kong, and add to the local art community.

I’d like to hone in on the word “experimental.” You once mentioned in an interview that you would like to use Tai Kwun as an opportunity to foster "younger, edgier projects" in Hong Kong. How do you intend to implement this model in particular, and what are its challenges?

Tai Kwun has only just started, and at the moment we’re in the middle of installing the first big solo exhibition, “Six-Part Practice,” of Hong Kong artist Wing Po So, who explores Chinese medicine and pharmacology. Her interest, by definition, is non-commercial because the materials she works with do not last. It’s exciting to not only be able to give artists the space, but also the resources to realize large-scale projects and installations that they might find difficult to do in commercial galleries or museums. We also look to put artists in contact with our network.

In terms of challenges, there are a lot of incredible artists in and outside of Hong Kong that we would like to make projects with, but it takes time, and we’re only at the beginning of an amazing journey.

Different models of art institutions expand the cultural discourse in different ways. Do you see the non-collecting method of Tai Kwun as generating a different perspective to the cultural narrative of Hong Kong?

I hope so. Again, it’s difficult to look into the future. In Tai Kwun, we have a lot of very interesting opportunities. On the one hand, the operation is for the young and mid-career artists, and for the art community. On the other, we are in a very unique position where we are part of an incredible art and heritage project.

We have many people come to visit us, not because they are interested in the art or exhibitions, but because they are interested in the amazing architectural compound and heritage site. A lot of people come without having any plans to see contemporary artworks, and that’s a very new challenge that is part of Tai Kwun, which not a lot of art institutions have to tackle.

What we’re grappling with is this: How do we engage a large number of visitors who have no previous experience with contemporary art? And how do we work with them via programs and education to make it a meaningful enough experience that they would become curious and want to come back again in the future?

What initiatives are being taken to engage the local community?

We have a variety of local communities. We’re in the middle of Central, one of the busiest commercial hubs in Hong Kong, but we are also located in a residential area where people who live around the compound come to visit our spaces. We certainly want to become the kunsthalle or museum for the local community here. Then, we also have the Hong Kong art community. Everywhere in Hong Kong is accessible within one hour or so, and we’d like to communicate and engage with them to produce interesting discussions and projects.

Aside from the booklets and wall text, Tai Kwun will also run programs that accompany every exhibition. “Art After Hours” is a public program series that will happen every Friday night, and includes talks, film screenings, discussions and music events. We hope to let people know that something interesting will always be happening every Friday evening at Tai Kwun Contemporary. I think offering some regularity where people can just come and enjoy themselves will be a very good way to engage the local art community.

Our heritage team will also hold exhibitions and programs that will bring and nurture new audiences who will hopefully become more interested in art and heritage preservation. Our programs are very cross-departmental so it will be interesting for both us and our audience.

Tai Kwun's inaugural exhibition, "Dismantling the Scaffold,” will be presented in collaboration with the nonprofit organization Spring Workshop, which closed its doors in late 2017. It seems organic, and almost symbolic to see the two spaces—one opening, one closed—working together to provide an arts platform for the public. Could you speak more about Tai Kwun’s collaborative model, and its exhibitions and programs with Hong Kong’s independent art spaces?

It’s important that we are working within a collaborative model, which means that we, ourselves, are not curating the exhibitions. It is very exciting to work with all these other institutions, inviting them to do projects in our galleries. Each program we’re going to make this year and for the next two years will be curated by another art institution. Most importantly, they are curated for Hong Kong. As I always say, we are not a pit-stop for traveling exhibitions. I firmly believe that all our exhibitions that we produce must reflect the place and time we are in.

For the show I previously mentioned, “Six-Part Practice,” which showcases the works of Wing Po So, we’ve collaborated with the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The show you mentioned, “Dismantling the Scaffold” is also another great example, presented by Spring Workshop and curated by Hong Kong curator Christina Li. It puts two different chapters of Tai Kwun into one exhibition: there is the celebratory idea of taking down a scaffold and building up something new, but the scaffold also stands in as a metaphor of a prison cell, touching upon the fact that we are, in fact, at the site of the former Victoria Prison. There are certain works that talk about the pain of imprisonment. Some works were called in from other spaces, some are reproductions of past works and some are completely new creations. In the end, what we want to do is to give both Hong Kong and overseas artists a chance to make something new that they wouldn’t be able to produce anywhere else. After all, that’s always the biggest joy for anybody making exhibitions.

How does one plan exhibitions in a space that is still being built?

We’ve tried out different things, testing the spaces, our procurement process and also the way we communicate with each other between departments. We had a rehearsal, which wasn’t a regular exhibition, but exactly what the title suggests—a testing of the site. It was extremely useful in understanding how to navigate internal administration, how to work with the space, sound and the video systems. You always figure it out, but you need to learn to figure it out in better ways—and through the rehearsal, we learned how valuable these experiences can be.

As head of arts at Tai Kwun, what are some upcoming exhibitions and programs that you are personally excited about?

We have a lot of things going on across every level, from really young family workshops to artist presentations, exhibitions and academic courses. We are currently in the process of planning the next ten exhibitions that will take place until the end of 2020, which is very exciting. Our inaugural exhibitions are two smaller shows each curated by a young Hong Kong art organization that responded to our open call; next year, we look forward to two solo shows by established Asian artists.

I also look forward to using our collection of Asian artist books in our Artists’ Book Library, which is a public library open to all. We’ve had several projects involving art and artists’ books in the last two years, and found that this is a really exciting way to engage a wider audience and attract people who would maybe not normally visit museums, so we plan to have many more projects like these in the future, starting with an Art Book Fair at Tai Kwun at the end of 2018. Our summer academy, which is basically a post-grad program with a two-weeks intensive course involving incredible art history professors, is also something I’m excited about.

Julee WJ Chung is the assistant editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tai Kwun opens to the public on May 29, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.