Ideas

Made Undeniable: Interview with Pio Abad

For the Philippine-born and London-based artist Pio Abad, historical archives are a source of inspiration. In particular, Abad’s multimedia works re-interpret the significance of objects in telling and shaping collective memories. Over the past several years, he has constellated the impact of the dictatorial reign of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos on the Philippines. By examining their regime's remnants, Abad aims to reveal and explore historical gaps.

During his three-month residency with Kadist San Francisco this year, Abad continued his dissection of the Marcoses’ political rhetoric via the study of historical materials. Delving into Bay Area archives as well as California-based libraries, he explored San Francisco’s past as a site of political resistance against the Marcos regime. In June, he presented a newly commissioned body of works at Kadist—the culmination of his research during his residency—including paintings, sculptures, and installations. On the occasion of the show, AAP sat down with the artist to discuss his process, methodology, and the stories he uncovered while in California.

The title of your show at Kadist is “Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite,” which is borrowed from a Romanian proverb. It's also the title of the book by journalist and foreign correspondent Edward Behr (1926–2007), which details the dictatorship of Romanian communist politician Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife, Elena. There’s a peculiar parallel that is drawn between the kleptocracies of the Ceaușescus and the Marcoses by way of this reference in the show’s title. Why did you choose this name?

The title of the show became a framework for me. “Kiss the hand you cannot bite” suggests an intimate relationship, but also a submission to power. I’m exploring interrelationships and friendships through the lens of empire. When thinking about the title here in San Francisco, the relationship between the Philippines and the United States came into the picture, as well as Nancy Reagan’s friendship with Imelda Marcos. Beyond that, the saying relates to the power dynamic that inevitably exists for Filipino-Americans and the concept of what it means to be a “good immigrant." What happens, for instance, when you start treating the site that has become your new home as a site of resistance to a regime that the US has enabled? In the show, I am considering these expansive, historical narratives and their relation to the body.

Previously, you’ve used replicas of paintings, handbags, and scarves to detail the corruption of the Marcos regime. Do symbols from your past works show up in your commissioned pieces at Kadist?

The show expands on some concepts I was working through in a recent project where I collaborated with my wife, Frances Wadsworth Jones, a jewelry designer, for the Honolulu Biennial. We remade 24 pieces of jewelry that Imelda tried to smuggle to Honolulu when she was granted exile by the Reagans in 1986. Some thought we recreated the jewelry pieces through a three-dimensional scan of the existing jewelry but we didn’t. We made them from scratch, so to speak. They are copies we created referencing online sources, sometimes a single jpg. The scale had to be imagined, and the depth of the facets had to be interpreted. At Kadist, the focus is on one of the bracelets, scaled-up as a concrete sculpture. For me, it’s a monument to a variety of things, such as corruption, and US-enabled fantasy and exile. It’s the largest piece that Frances and I have ever made.

To create the works in this show, you worked with local and state archives, poring over their records, and collaborated with local historians. Tell us about your research process. What role do these partnerships play in your practice?

I was really excited to be working in San Francisco where there is one of the largest Philippine diasporas. The city served as a site of resistance against the Marcos regime. People met here and a lot of resources were pooled together to underwrite civil movements in the Philippines. One of the privileges of being an artist is being able to create a one-to-one interaction with the people who have produced or collected historical objects. If and when possible, these relationships become part of the work. For example, I met with Kim Komenich who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his photo reports of the EDSA Revolution in 1986 [also known as the People Power Revolution—a series of mass demonstrations in the Philippines against the Marcoses’ use of violence and electoral fraud]. I also spent many hours visiting the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, to which Kim donated his entire negative catalog. So much of how I remember the revolution was largely through his images and there’s a really great sculptural language in his photographs. One of his photos from 1986 really grabbed me and is represented in the show.

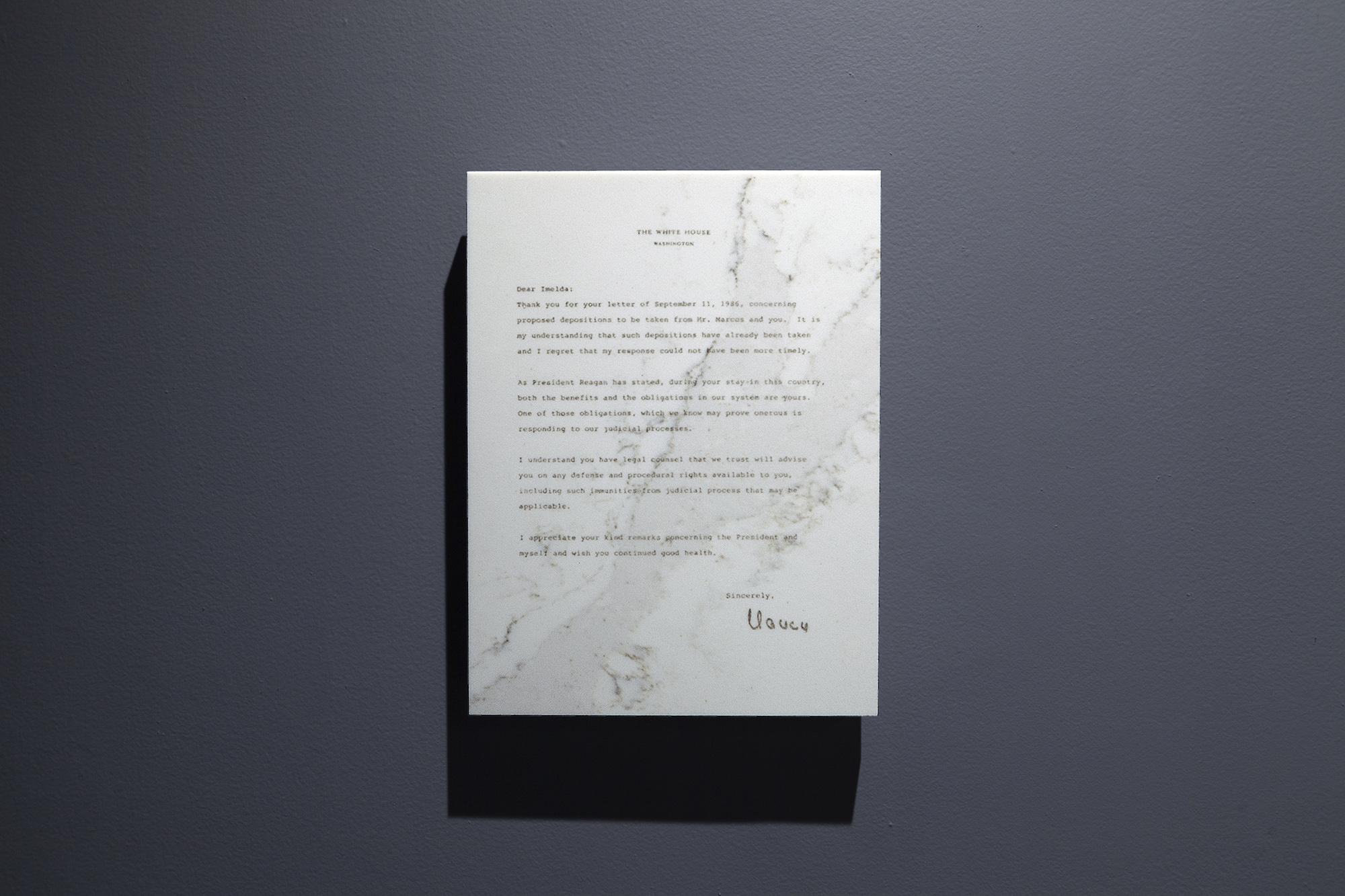

In addition, I spent some time in Simi Valley scouring the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum archives. The Reagan-Marcos alliance was a strategic move on the part of the Reagans, but they also appear to have had a true friendship. A lot of the decisions that had to do with the Marcoses being whisked off to Hawaii—based on my research in the archive—was a gesture of their strange friendship, which may have been rooted in a shared obsession with image-making. When I was going through the letters, I found some interesting stuff, but a lot is redacted. There are A4 sheets of paper saying, “This document has been withheld for security purposes.” What’s interesting about looking at these archives from an artist’s perspective is that what hasn’t been redacted explains so much, particularly the intimate letters from Nancy to Imelda. You’ll find details of objects they gave each other, like Imelda's gift to the Reagans of a larger-than-life American Eagle sculpture made out of seashells (which I plan on seeing, actually). As much as this is a story of Philippine history, it’s also a narrative about these characters from the US.

In fact, the narrative threads of many international civil movements cross through the US. I explored an amazing book shop in San Francisco's Mission district called Bolerium Books, which has a collection of California-produced books and pamphlets from across various histories of resistance. There’s Anti-Marcos and Anti-Reagan literature to Pro-Sandinista posters. Like when people from the Philippines came to the city to organize against the Marcos dictatorship, people from Nicaragua and El Salvador landed in the Mission as refugees, largely from the same kind of misguided alliances that the US made in those regions.

I also spent time with Mary Valledor, the widow of Leo Valledor [a Filipino-American painter who was born and raised in the Fillmore District of San Francisco]. I’m researching Leo’s practice, and through this, trying to understand how histories of erasure occur. His history of art making is a very specific one related to contemporary art and the avant-garde—he was involved in the Park Place group in New York City where artists like Sol Lewitt and Mark di Suvero also had their start. I have been thinking about his work in relation to what gets edited out of history and how this history of erasure fits within the narrative of the American empire. I’m not going to justify why it necessarily fits with my exhibition, but I hung a Leo Valledor painting in a separate gallery as a parallel exhibition to “Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite.”

What are the consequences of re-remembering, or remaking forgotten or stolen objects?

There are really interesting overlaps between artistic work and historical image-making. For example, during the Honolulu Biennial, Sherry R. Broder, the attorney who successfully prosecuted the Marcoses for torture charges, came to the opening, saw the pieces of jewelry, and said, “Oh wow, I’ve been looking for these!” My work becomes another way of recording and archiving.

The show at Kadist is exciting because while there was the same archival rigor in my process as with previous exhibitions, this is my most material show. There are concrete sculptures, photographs, and paintings. They function as art objects but are also the archive made even more visible, materially incontrovertible and less deniable.

Pio Abad's "Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite" is on view at Kadist, San Francisco, until August 10, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.