Ideas

M+ Matters Talk Recap: Hidden Histories of the Mao Era

China is well represented in the international ranks of the (newly) mega-rich, and is known for its global trade and exports. These phenomena have been put down to the implementation of Gaige Kaifang (“reform and opening up”) in 1978, but was the nominally socialist country truly as impoverished and cut off from the world before then? This was at the center of the issues tackled in the latest M+ Matters public talk, titled “Post-1949 Visual and Material Culture in China,” moderated by Denise Ho, assistant professor of history at Yale University, and M+ curators Pi Li and Shirley Surya, with a panel comprising Karl Gerth, the Hwei-Chih and Julia Hsiu Endowed Chair in Chinese Studies and professor of history at the University of California San Diego; Jennifer Altehenger, lecturer in contemporary Chinese history at King’s College London; and Zheng Shengtian, adjunct director of the Institute of Asian Art at Vancouver Art Gallery.

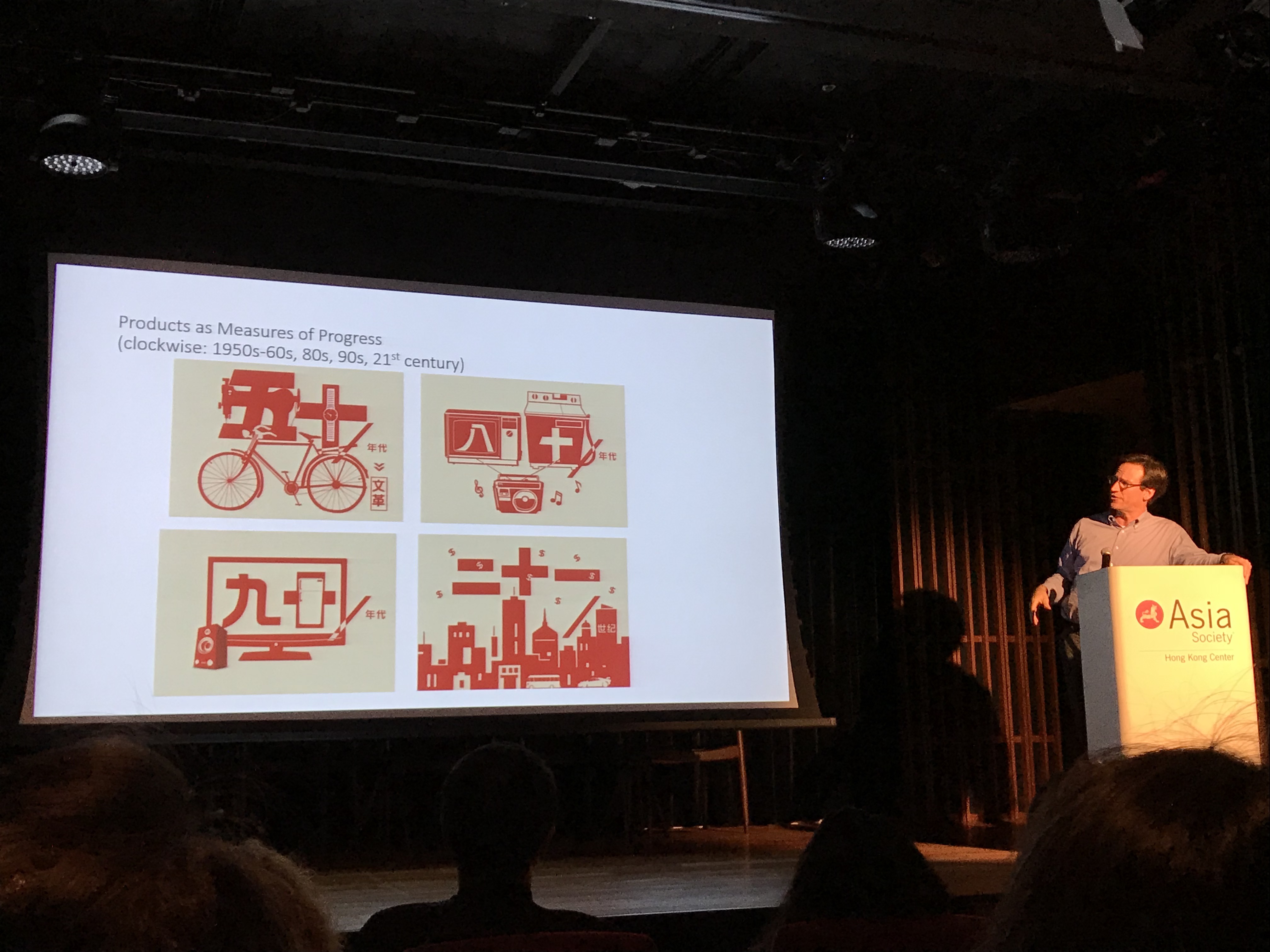

Gerth’s opening presentation systematically challenged widely accepted paradigms about the lived experience of baixing (commoners) in Mao-era China. Gerth argued that a “bourgeois consumerism” existed even before the country’s “opening-up” in the late 20th century—material consumption had not simply disappeared with the inception of the Chinese Communist Party’s republic. This consumer culture is represented in the sandajian (“three big pieces”), a term that emerged in the 1950s referring to the “it” items that became status symbols and a social currency within peer microcosms. From the 1950s to ‘70s, the sandajian were the wristwatch, bicycle and sewing machine—items that respectively allowed for a modicum of personal style, facilitated mobility, and enforced gender roles within a petit-bourgeois family unit. The emergence of such a culture, argued Gerth, is symptomatic of a wider push towards modernization separate from political ideology.

Similarly focused on material culture, Altehenger examined China’s participation throughout the 1950s at the Leipzig trade fairs in then-East Germany, where it had the chance to project an image of successful modernization and prosperity through the items presented, from heavy machinery and electrical appliances to furs, silks and jade—more a political message directed at international audiences (including other socialist countries) to indicate the superiority of China’s socialist system than an accurate reflection of economic realities. In the ensuing discussion, Gerth pointed out that the idea of “products as measures of progress” fits within a larger narrative of a race to modernize that contradicts tenets of socialism, precipitating a debate as to the validity of analyzing China through the lens of its official ideology, with the moderators making little headway in bringing the discussion back to the main topic of material and visual culture.

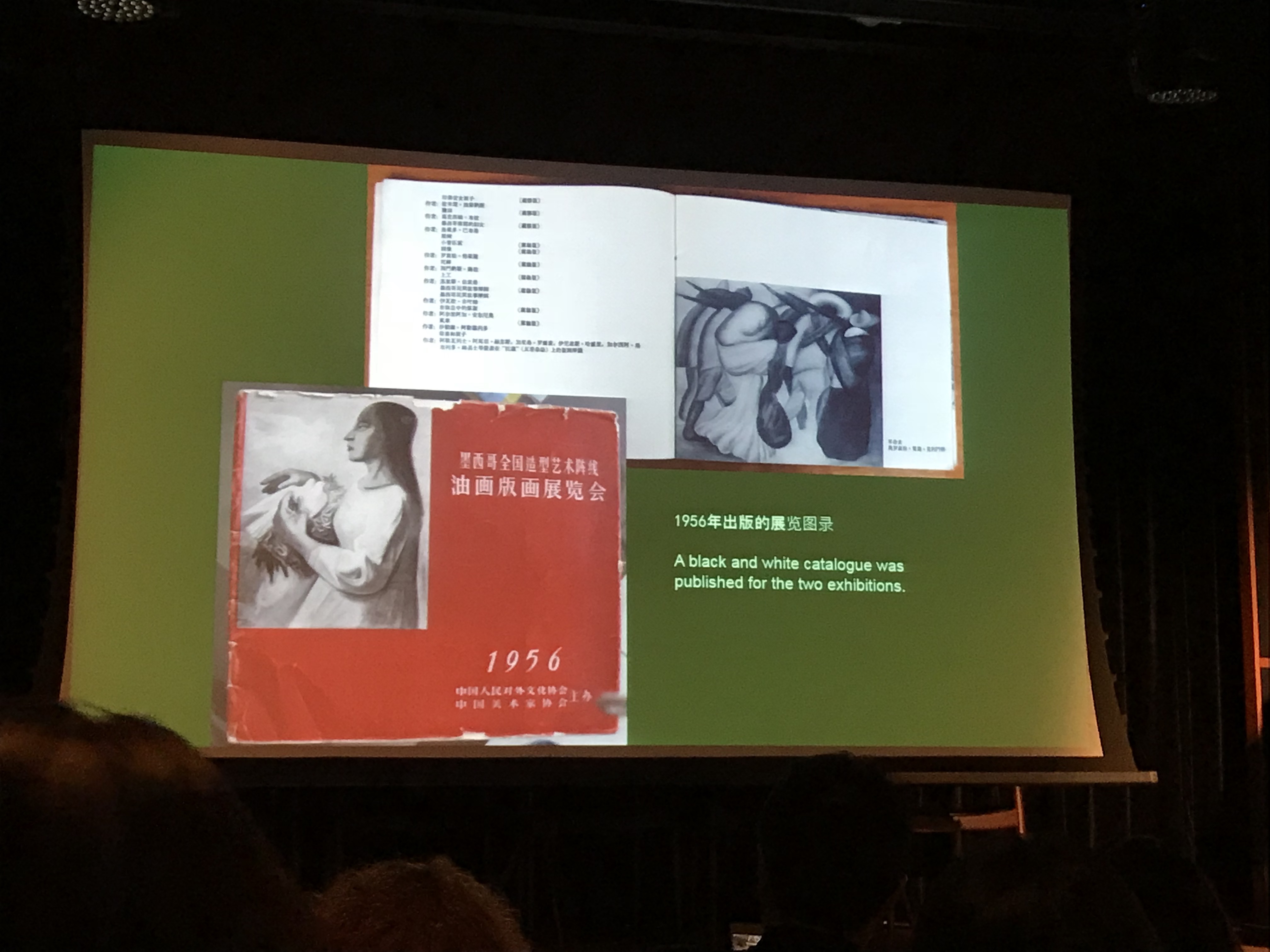

Zheng’s final presentation revealed the little-known story of the influence of the Mexican Mural Movement—which tended to promote left-wing ideas of political and social revolution—on China’s avant-garde artists throughout the 1930s to ‘50s. Leftist writer Lu Xun, a key figure in modern Chinese literature who was posthumously celebrated in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), circulated an image of Mexican painter Diego Rivera’s fresco, Night of the Poor (1928), in Beidou literary magazine in 1931. As part of a wider belief in the democratization of culture, Lu championed Mexican muralism because he considered it as a truly public art form, not exclusive to the learned elites as ink or calligraphic arts had been. This initial break from a purely Chinese tradition gave momentum to the development of Chinese avant-garde art, culminating in two large-scale Beijing exhibitions held in 1956 that displayed 138 paintings and 258 prints from Mexico (attended by first Premier of the PRC Zhou Enlai, no less), thus showing how Chinese visual culture was dynamic and responded to foreign exchange.

Overall, the panelists agreed that a pervasive narrative of China’s isolationism and path to socialism in academic history needed to be reconsidered. Each of the presentations revealed lesser-known histories that did not necessarily fit into established notions of the lived experiences and political narratives of Mao’s China, challenging the historiography of the country as a whole.

Christie Wong is an editorial intern of ArtAsiaPacific.