Ideas

Jakarta Lore

Every day, our world drifts more into crony capitalism. Oligarchs privatize power as politics become a maniacal performance. Dissidents are extinguished by police forces as state-sponsored thugs roam free. Even its opulence seems as vapid as its tiny seductions. When did this fever dream start? Journalist Vincent Bevins and film director Joshua Oppenheimer pinpoint the Indonesian massacre of 1965–66, which exterminated up to one million civilians as the rupture that still afflicts the nation and the global world order.

Bevins’s book The Jakarta Method (2020) offers the geopolitical context: 1955 saw a historical optimism epitomized by the Bandung Conference, during which, ten years after President Sukarno unified Indonesia, he gathered other newly independent Asian and African states into a movement for anticolonial freedom and Cold War non-alignment. At home, he preached “Nationalism, Islam, and Marxism,” syncretizing an “Eastern nationalism” that is interracial and multicultural. He was tolerant of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), which rejected armed struggles and engaged through mass educational, cultural, and agricultural programs. The two power blocs had had their time; the Third World was to be the coming utopia.

As the Vietnam War escalated in the late 1950s, Washington DC became more hostile toward the neutral leader. After the CIA had discussed Sukarno’s assassination, and its covert bomber aircraft was shot down over the Indonesian archipelago, the United States moved onto indirect tactics such as giving ideological and technical training to Indonesian Army officers in Kansas.

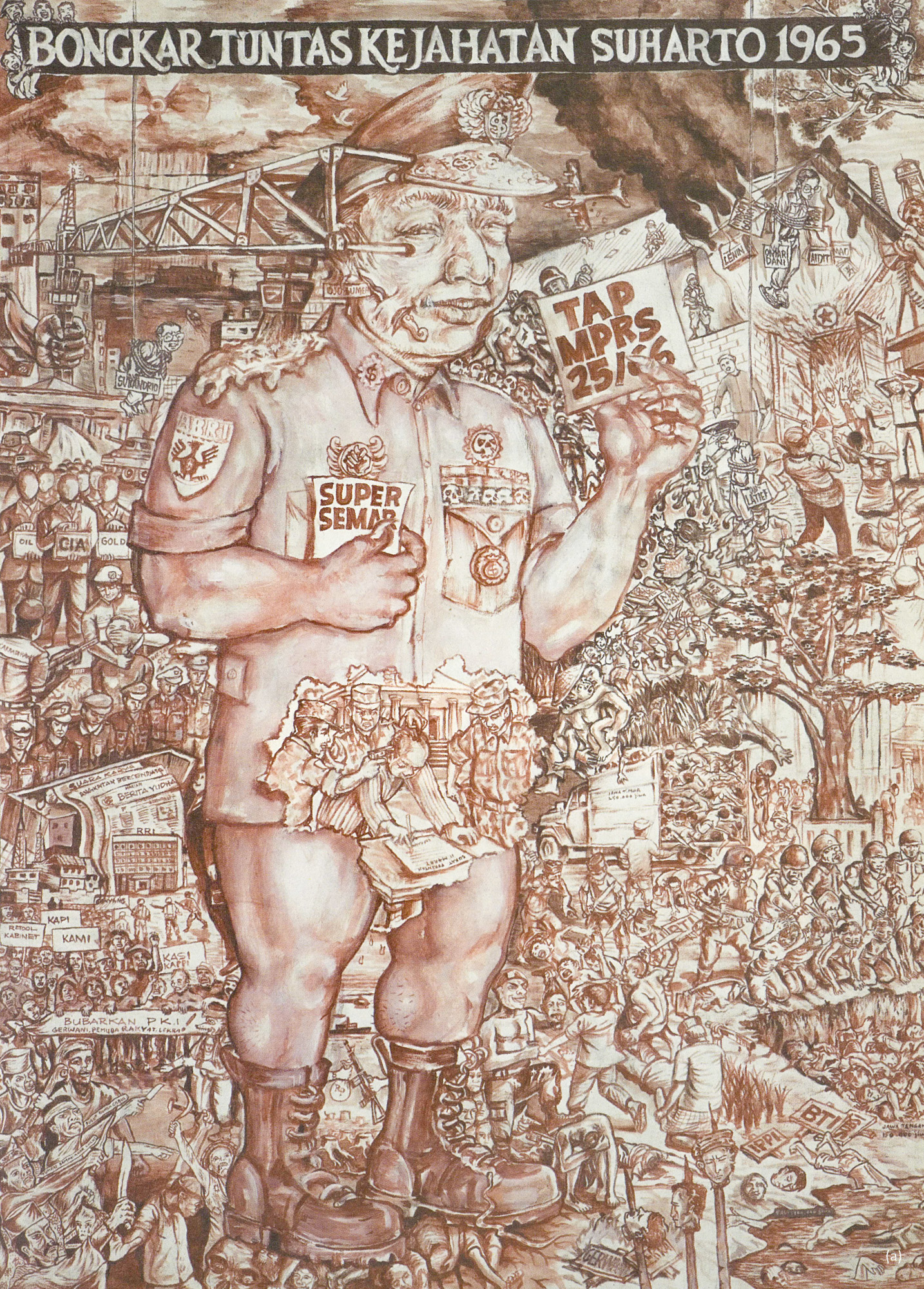

The rupture arrived in 1965. Following the kidnapping and murder of six army generals by troops from the 30 September Movement (G30S), General Suharto falsely accused the PKI of organizing an attempted coup d’état. This led to a nationwide anti-communist purge in which the army and paramilitary gangs systematically slaughtered civilians accused of having leftist sympathies.

Bevins proposes that “disappearing” people as a tactic of state terror was deployed for the first time in Asia. Up to one million unsuspecting people across Indonesia were brought in or turned themselves in for questioning, and then tortured, killed, and dumped into rivers and mass graves. Another million were herded into concentration camps. Oppenheimer’s documentaries close in on the carnage. For The Act of Killing (2012), the director invited members of a death squad to re-enact their atrocities for the camera, Hollywood-style. One unremorseful leader recounted machete beheadings, which he deemed messy and inefficient. The murderer of 1,000 people instead boasted about inventing a strangulation contraption.

The Suharto-led military compounded the exterminations with dehumanizing lies. Controlling the media, they claimed that the PKI had planned for a violent takeover and held demonic rituals. Members from Gerwani (Women’s Movement) were vilified as seductresses who danced seductively before killing and mutilating the six generals, castrating them and gouging out their eyes. Such propaganda contributed to the immediate violence and continued after 1967, when Suharto took power and began a 31-year dictatorship. In addition to a holy monument, a gory docudrama titled Treachery of G30S/PKI (1984) became mandatory viewing for students annually. Fanatical anti-communism became a national law and mythology, and survivors of 1965–66 are shunned by their neighbors.

The global importance of this murderous campaign cannot be understated. The then-third-largest communist party in the world was annihilated in “A Gleam of Light in Asia,” according to The New York Times. The US savored the victory in which they were complicit, having supplied kill lists, arms, psyop assistance, and conditional aid. Ambassador Marshall Green even expressed respect for the Army for “carrying out this crucial assignment.” Almost immediately, Suharto welcomed foreign industries and held an international investment conference. Freedom for the Third World became freedom for the market. Taking notice, Asian and African leftists lost faith in non-alignment and shifted to radical militancy.

The “Jakarta Method” proliferated across the world. Bevins identifies a similar takeover in 1964 in Brazil. Purportedly suppressing a leftist revolt and satanic communists, the military ushered in a 21-year dictatorship and adopted “Operação Jacarta” as code name for its covert communist extermination strategy. In Chile, “Yakarta viene” was graffitied around Santiago, and right-wing radicals sent out threatening postcards printed with “Yakarta se acerca” and a fascist-style, geometric spider logo. A CIA-backed coup led to General Pinochet’s 17-year dictatorship. His military junta joined up with other South American regimes in Operation Condor, practicing interstate terror to protect the Americanized world order.

And what are the spoils? Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing depicts the present Indonesia. Not only are the killers not persecuted, paramilitary organizations actually hold power in the government. Ministers brag about corruption while gangsters are praised as “free men.” They flaunted lifeless crystal figures and plastic-wrapped taxidermies as proofs of their wealth. The companion documentary The Look of Silence (2014) follows an optometrist, whose brother was slaughtered, as he cared for his ostracized family and confronted the village killers. The guilty ones tried to rationalize their sin by blaming (false) historicism, a chain of command, and pre-agreed stakes of war—only it wasn’t a war. The bloodshed's psychic trauma lingers in Indonesian society, among a sprawl of shanties and malls.

Oppenheimer sees history as the stories we tell ourselves. Re-enacting the killing and staging the reactions, his films are almost devoid of context. His subjects are put into dreamlike situations, forcing a counter-performance toward their perceived continuum of history. One killer reacted by vomiting as he re-examine his actions. Viewers are thereby shocked and shaken to reconsider the acts, looks, obscenity, and official narratives in their world.

In contrast, Bevins assembles a trove of testimonies and evidence, thereby piecing together an often forgotten past. Most importantly, the book features in-depth investigation and tells the history through phenomenal personal accounts. The mere attention paid to the afflicted’s life stories serves to restore their humanity and historical spirit. One tragic example is the young girl Ing Giok Tan, who set sail from Jakarta across the world to São Paulo, witnessing the violence of the Cold War in all its brutality. The writer met her again in 2008, when the 58 year-old Brazilian was marching in a rally against the former military commander and future Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro.

To date, the Indonesian government has yet to offer an apology for the mass killings of 1965–66, let alone retribution. Granted, the work by activists and documentarians have prompted local investigations and declassification of US documents. In comparison, reconciliation did happen in much of South America. In Brazil, a socialist was just elected president again. While the Jakarta Method’s depressing legacy prevails, there’s much work to be done to heal its damage.

Curated by an ArtAsiaPacific editor, “Lore” is a biweekly blog that probes into the histories and mythologies of media.