Ideas

Gentle Sweeps in a Deep Abyss: Interview with Dino

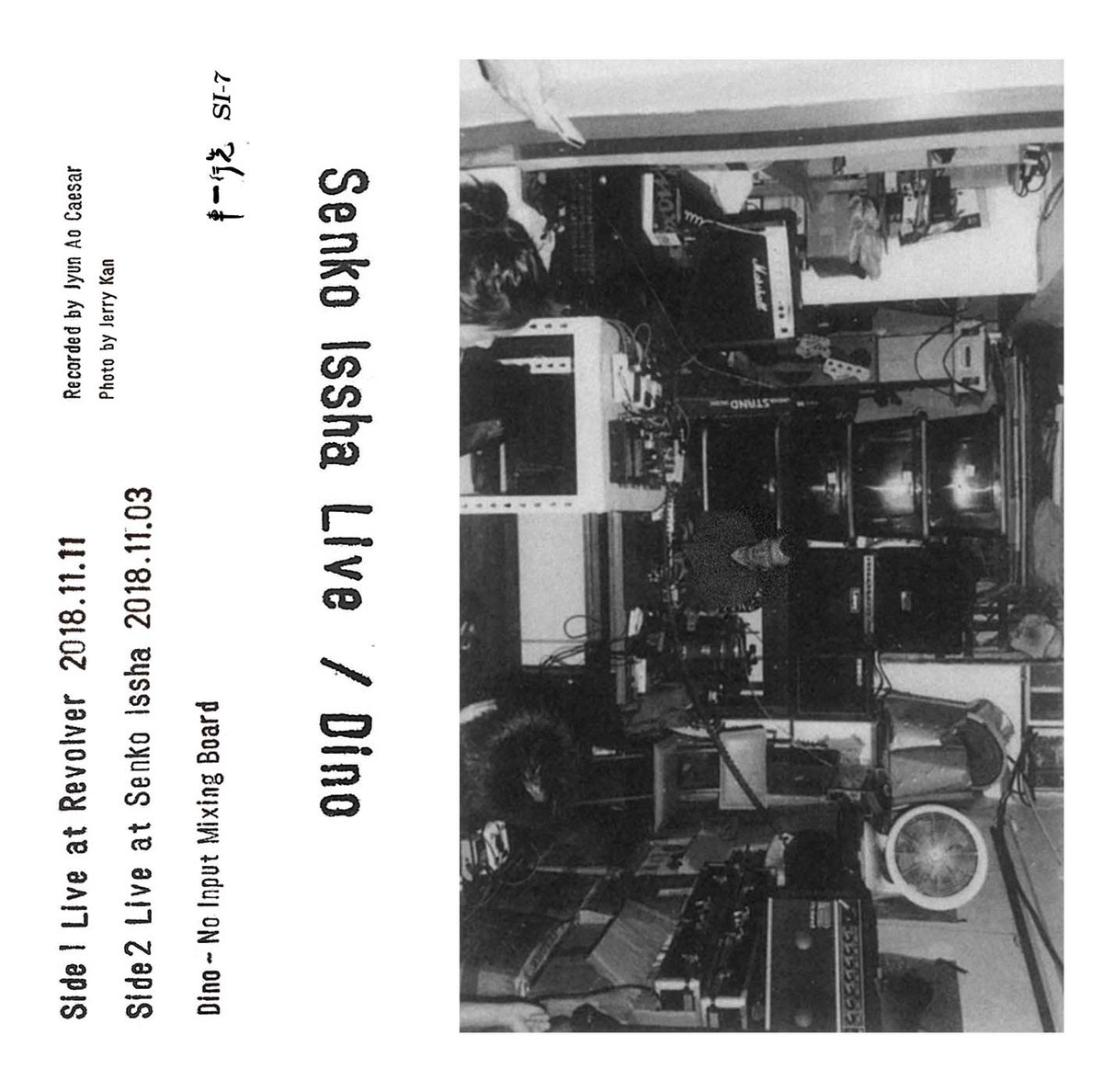

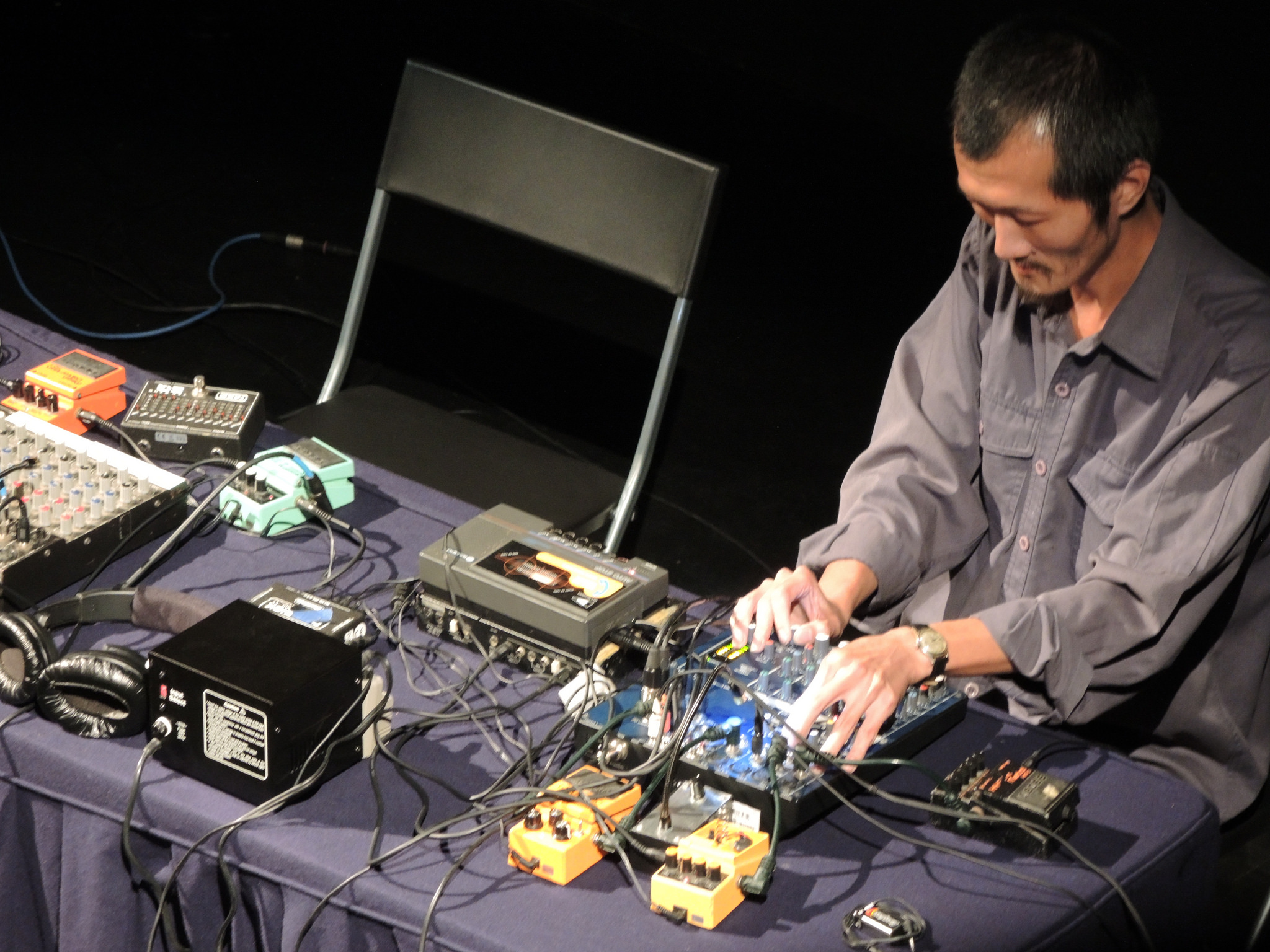

Taipei-based Dino, otherwise known as Liao Ming-he, is a prolific noise performer who has been active since the 1990s, and is a significant figure of the Taiwanese noise scene. With a distinct sound palette and innovative approaches to manipulating sonic space, his instrument of choice is a mixer board that has no input and is instead hooked up to a series of effect processors that create evocative articulations of internal feedback. Dino’s latest album Senko Issha Live / Dino (2018), produced by the independent Senko Issha, is his first label-backed record. Released in the last quarter of 2018, the album features two exceptional solo performances that capture his persistent search for new sound.

AAP sat down with Dino to discuss his boundary-pushing process, and his thoughts on noise, improvisation and the art of listening.

Looking back, what was the Taiwanese noise movement like in the 1990s?

The first, second, and third wave of Taiwanese noise—these are terms and academic arguments that have appeared in recent years. Back in the day, there were very few people involved. The scene only grew larger when we started performing at ET@T [an artist-run space established in 1995 in Taipei City with the mission to support digital art]. Oftentimes the audience consisted of people who made music themselves. The end of the first wave of Taiwanese noise and the beginning of the second are marked by the Post-Industrial Art Festival organized by Lin Chi-wei and Wu Chung-wei in 1995. It was around that time that Lin and others started making electronic music and experimented with many things, like quadraphonic performances and multi-directional setups. Lin and I both agree that we have done too many bad things in the past. There was always a feeling that we were going to hell after every performance. Now we would like to clean up our acts.

You once described performing as a kind of xiu xing (修行), a Chinese term that roughly translates to self-cultivation. What does this term mean to you?

When the same motion is repeated over a period of time, it generates a certain amount of feedback. The action, done over and over again, will also eventually harden. Some people call this kind of repetitive practice xiu xing. With or without performances ahead, I go through the same motions at home and play with my equipment everyday. They are laid out on my desk and never stored away. Over time, my daily practice generates feedback—some element will return in the process, or maybe it won’t. In any case, what I do disrupts my rhythm of life—I would like to set a start and finish time every day, but more often, I play without end and miss dinner. One can sustain this level of passion for one, three, five years; if you can continue into the sixth year, I have deep respect for your radical fanaticism.

For several years, I played around with other things, including calligraphy; seal carving; and the craft of guqin, a string instrument that is attributed to China. Seal carving is very interesting—to me the experience is similar to noise. In the process of slowly chipping away at stone, you create a sound that you can hear not only through your ears but also through your hands. That subtle, tingly feeling is addictive. After a while, I had to stop carving seals, because it was changing my personality and that was quite terrifying. It made me very anal and picky, which made life too tiring.

What are your thoughts on your recent album Senko Issha Live / Dino?

This is my first album released by a record label. In the 1990s, I made a few albums myself. They were limited edition tapes recorded in my studio, and most of it was ambient noise. On one occasion I made a dozen unique tapes while listening to the sound of rain falling on my roof. I repeated this process in another project, creating a series of tapes in relation to one observational point.

My new album includes two recent performances organized by Senko Issha. They happened within one week of one another, and on both nights, I was in a similar set of mind. Side B happened in Senko Issha while Side A was recorded at Revolver, a Taipei music venue. Prior to the Revolver performance, Wang Chikuang, the owner of Senko Issha, told me the lineup was made up of noise musicians. So, in order to complement the situation, I decided to add a fuzz processor to my set. I would say what I do is noise, and that I am punk, but I do not have enough anger to be truly noise or punk. I never had enough anger, at least not enough to form a punk band or make real noise. What I do cannot be sustained by anger, it is not who I am. But I would still say that I make noise and I am punk, because these imaginations cannot disappear, they are what I reach for—if they are thrown away, there would be too much room for change.

Can you speak about your process with no inputs?

The kind of thing I have been doing is quite simple. Using a stereo system, I pan all my sound to one speaker and then use delay to spread it across space and time. Only the first beat of sound you hear is real and the rest is fake, created by effects. Eventually the time difference between right and left speaker evens out and what you end up hearing is something like a wall of sound. Your ears might trick you to think there is still a delay between the two speakers but that is just an illusion. In order to achieve this, the frequency of sound must make the room vibrate. For some time, I would take off my shoes to find the right sound, then begin my performance. What I do depends on the conditions of the space.

Even though I improvise, I do not like the term—in fact, I detest it. In my listening experience, what is described as improvisation often turns out to be more like new-age music. For example, a chord is introduced and maintained until the end. Sometimes this may last up to one hour, and in this timeframe, there are changes in the tonality but not a lot of musicality or interesting sounds. I’d rather go to Taichung and partake in the Indigenous gatherings that involve collective singing. There is much more improvisational merit to their kind of music. There is always someone singing off tune while striving for unison, creating many interesting changes.

What goes through your mind during a performance?

Many rock musicians come to my house to drink with me and complain about things. These are friends I’ve known for some time. They drink on a daily basis, and yet, before going on stage, they insist on a mental state of clarity. Their thinking goes against my understanding of performance. I drink before a show to dull my reflexes, otherwise it would feel like attending a school examination. Presets of perfection do not exist in rock music, or classical music, or any kind of other music performance, unless you have a strong motive, such as if your performance is a stepping stone to meet someone’s expectations. In that case, you must act precisely, but that would be an examination, not a performance. In actuality, I cannot let go of many habits when I perform. These are not habits of listening but habits of my hands. Sometimes when I drink to a certain state of mind, I am unable to suppress my hands from certain motions, and I allow more waiting time in between gestures, which makes for a quieter performance.

What are you working on now?

I am picking up on projects I started long ago, things I’ve always wanted to do. I am looking for new sounds and trying to lock them down. The setup I am using now is inspired by a sense of emptiness I felt after I performed at Asian Meeting Festival in Taipei last August. The emptiness was so strong and relentless, it was as if something that I had insisted on for a while had suddenly been struck down for no reason. So I spent the next few weeks working and invited a few friends over to test a new setup, which I am using now. This was of course not an act of resistance, because I am a man of self-abandonment. However, an abandoned person in a deep abyss will still quietly make gentle sweeps in the waters, creating ripples of dark sensibility. People on the shore may not be able to see these movements, but with close attention they can notice someone swimming beneath, and perhaps there is also someone swimming right above me, and someone swimming right below me, forming a vertical chain. As musicians, we always want someone to give us a hand. It is impossible for anyone to generate things by themselves; at least, it has not happened before, in my understanding. It would be terrible if there were only one chain of swimmers—the future would not look hopeful.

There are many artists today who say they work with sound, and so the question is, what is it that they want to control? Sound can be used to control people, but do you want to control people? For musicians, this question is not so urgent because they have music as their medium. But sound is something very immediate; when you are on a battle field, when you are facing death, it is not a matter of visual signals—you hear sound first. And perhaps, when in doubt, you will look for the source of the sound and stare at it, deciphering whether what you heard was real or not. Of course, there are those who are more visually-oriented, but the majority of ordinary people listen first, and use their eyes to seek validation. And that is something very unromantic.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.