Ideas

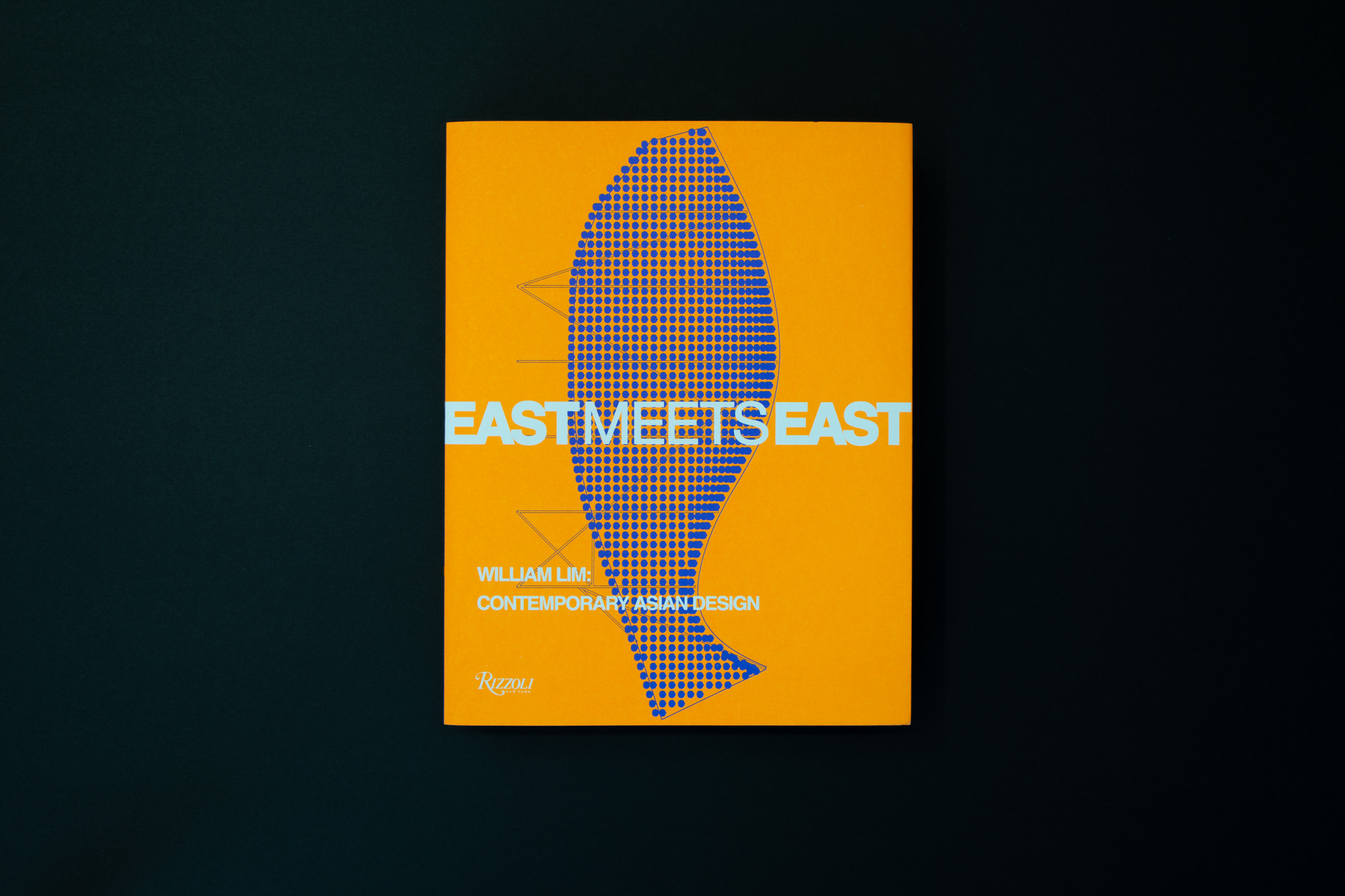

East Meets East: William Lim: Contemporary Asian Design

Within the first few pages of East Meets East: William Lim: Contemporary Asian Design (2022), contributor Catherine Shaw wants you to know: “This book is not a monograph.” The 400-page book includes five thematic essays by Hong Kong architect William Lim: “Heritage,” “Craft,” “Urbanism,” “Lifestyle,” and “Utopia.” The content is structured accordingly, thus thwarting the chronological order one would expect. There are additional essays by former director of M+ Lars Nittve, curator Aric Chen, architect Lyndon Neri, and artist Stanley Wong (otherwise known as anothermountainman), who also designed the book. While the book is light in text, it offers a generous collection of sketches and photographs of Lim’s countless projects. The book illustrates what seems to be the backbone of Lim’s approach as a designer and architect.

Lim begins with “Heritage,” stating: “Everything I do reflects my cultural heritage.” Born in Hong Kong and educated at Cornell University in the United States, Lim reflects on the various ways he tried to infuse his “Asian heritage” in all of his design projects. One of the examples he cited was the collection of mobile furniture—inspired by “push cars and mobile food stalls seen all over Asia”—that he designed for the 50th anniversary of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul. Lim leaves readers with this axiom: “Knowing one’s heritage or the heritage of a culture, and how to apply it, adds richness and depth to design.”

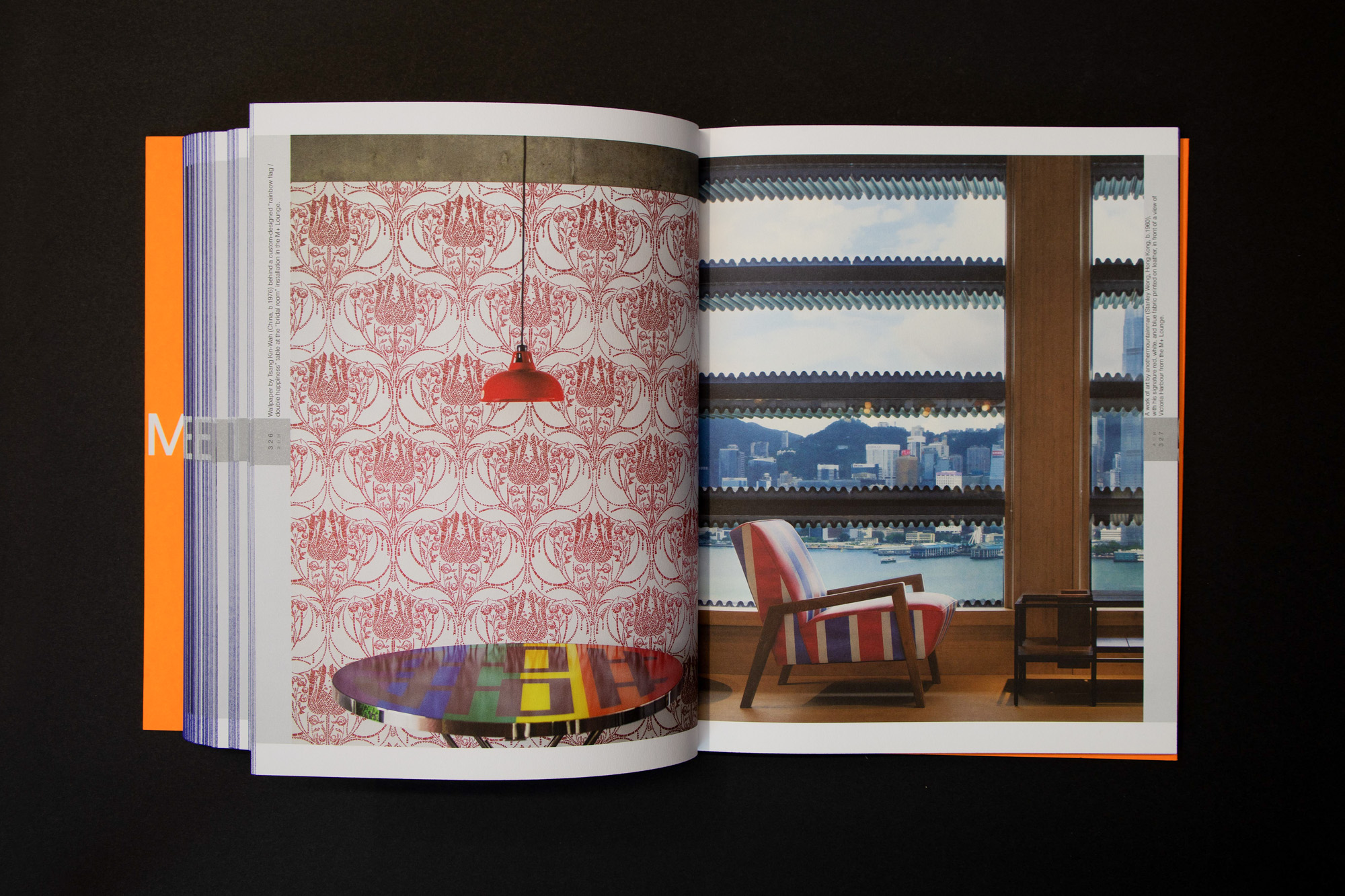

Moving to “Craft,” Lim highlights the craftsmanship of his practice and his network of sifu (Cantonese for master) who help him bring his designs to life. He emphasizes the importance of quality as well as his tendency to choose “simple elementary” materials, such as the plywood he used for the benches at Hong Kong’s Hotel ICON.

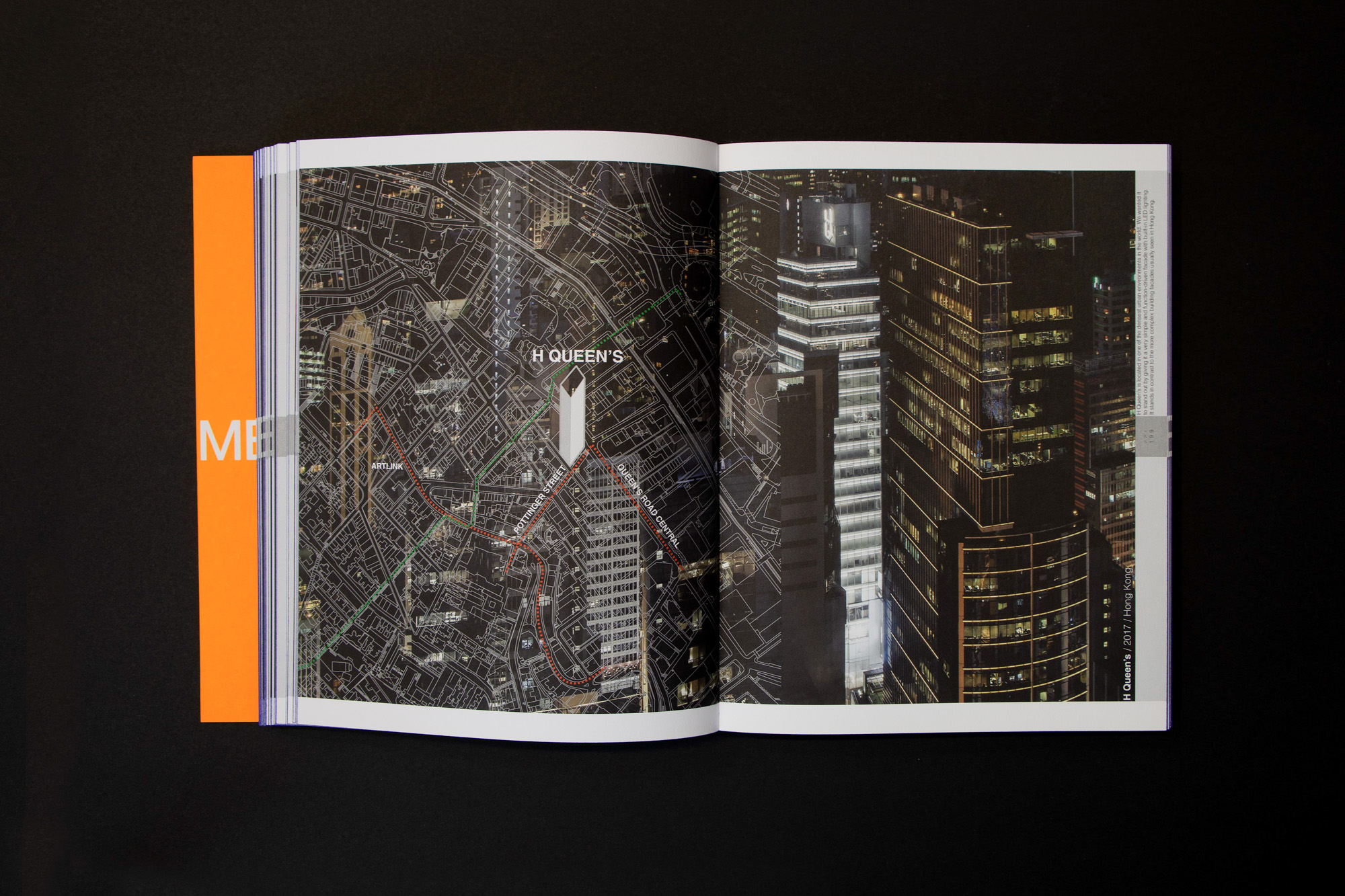

In “Urbanism,” Lim discusses the intricacies of designing buildings in Asian cities, which have a high population density, thus requiring efficiency, while maintaining the qualities Lim examined in the last two chapters. Lim includes examples from Bangkok, Hong Kong, and Tokyo.

The essay “Lifestyle” continues the discussion started in “Heritage,” but instead focuses on the living cultures of Asia, and the traditions, festivals, and superstitions that come along with it. In Lim’s practice, he states that he takes “lifestyle” aspects into consideration for his projects. For example, when designing Raffles City Chongqing, Lim created an “ink drawing of the imperial fleet arriving at today’s Chongqing’s Chaotianmen,” which served as a motif for the interiors.

In the final theme “Utopia,” Lim discusses the desire to strive for perfection, combining the development and preservation of craft and culture with a desire for sustainability. In the conclusion, he connects all the aforementioned themes with his definition of utopia, which to Lim, means “continually broadening and promoting designs and concepts that are indigenous, cultural, green, sustainable, and socially engaging.”

The short but thought-provoking themes provided an overview of Lim’s practice. One thought that was provoked a few too many times, however, was: what do the writers mean when they use the terms “Asia” and “Asian”? For a book titled “Contemporary Asian Design,” the two terms are never defined, and are used frequently and seemingly loosely, as the writers mainly cite East Asian and Southeast Asian examples, with most from Hong Kong and China. Case in point: the opening section primarily focuses on Lim’s Hong Kong identity, but includes an essay titled “A sense of a new Chinese renaissance,” on the development of architectural studies in China. Nonetheless, the book presents an extensive archive of Lim’s architectural practice as well as some of the iconic silhouettes of major Asian cities.

Tiffany Luk is ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor.