Ideas

Colomboscope 2024: Biennial as Import, Forest as Export

How can the global art community prioritize consciousness to avoid reenacting colonial impacts? How can the hosts of biennials sustain the global art network while preventing cultural exploitation from presenting predominantly international artists? Charles Esche articulates in his 2012 essay “Making Art Global: a Good Place or a No Place?” that the “biennialization” of the global art world presents a paradox for large-scale international exhibitions: the global art system is split into a future with broader cultural truths set by the minority international art community, which inevitably commodifies the “South” as a cultural fetish. Nearly 14 years after Esche’s essay was published, I visited Sri Lanka to take notes on the tangible “Southern only” opportunities, to learn about the land that has undergone generational extraction, and to seek alternatives in the global art ecosystem that aims to go beyond cultural fair trade for the transnational minority in the arts.

Slated from January 19 to 28, only one-and-a-half summers after the overthrow of the Sri Lankan government, was the 8th edition of “Colomboscope: Way of the Forest.” The theme took inspiration from Ursula K. Le Guin's classic sci-fi novel The Word For World Is Forest (1972), concerning the turbulent national affairs and the ongoing ecocide-al violence. While the state was recovering from the multifaceted collapse, “Way of the Forest” welcomed guests from international institutions, including Sharjah Foundation, Serpentine, Tate, Rockbund Art Museum, and MoMA, many of whom were visiting Sri Lanka for the first time.

Since its launch in 2013 as an annual multidisciplinary art festival over one weekend, Colomboscope has evolved into a 10-day program that is critically acclaimed in the region. Despite its connotation as a festival, the curatorial vision challenges the existing biennial models and delves into sociopolitical themes—negotiating between national identities, cultural and global trends, and economic success. In this edition, Colomboscope sought collective knowledge from Southern neighbors that are also resisting perpetual extraction and routine oppression, inspiring interdependence and survival strategies. Meanwhile, the festival’s critique of biennials as Western exports was accentuated by the nation’s ongoing crises.

In “Way of the Forest,” collectivism was manifested through a curatorial team with diverse South Asian perspectives: Sarker Protick from Bangladesh, Hit Man Gurung, and Sheelasha Rajbhandari from Nepal. Along with the artistic director Natasha Ginwala and assistant curator Vidhi Todi from India, the exhibition showcased over 40 artists, with most works commissioned by the festival and 48 international partners. The ambitious lineup of guest panelists based in Southern cultural contexts included Kenyan, Mexican, and Philippine artists, and topics from ecofeminism, to mushrooming, to subcontinental solidarities, voices of the global majority, were tactfully embraced by interdisciplinary programs across central Colombo.

The 10-day program, with minimal collateral events and immediate press coverage, became a rare opportunity for international guests to immerse themselves in the southern environment. The itinerary initiated critical exchange between participants, and the week facilitated discourse on decolonization amongst a focused and “imported” cohort. Although all materials were available in Tamil and Sinhala on site, it is worth noting that the exhibition publication was only printed in English, emphasizing the distance between the hosting communities. There was also hardly any mention of the recent national crisis nor the ongoing protests nearby the main gallery in the opening speeches, which became an elephant in the room considering the festival’s curatorial statement.

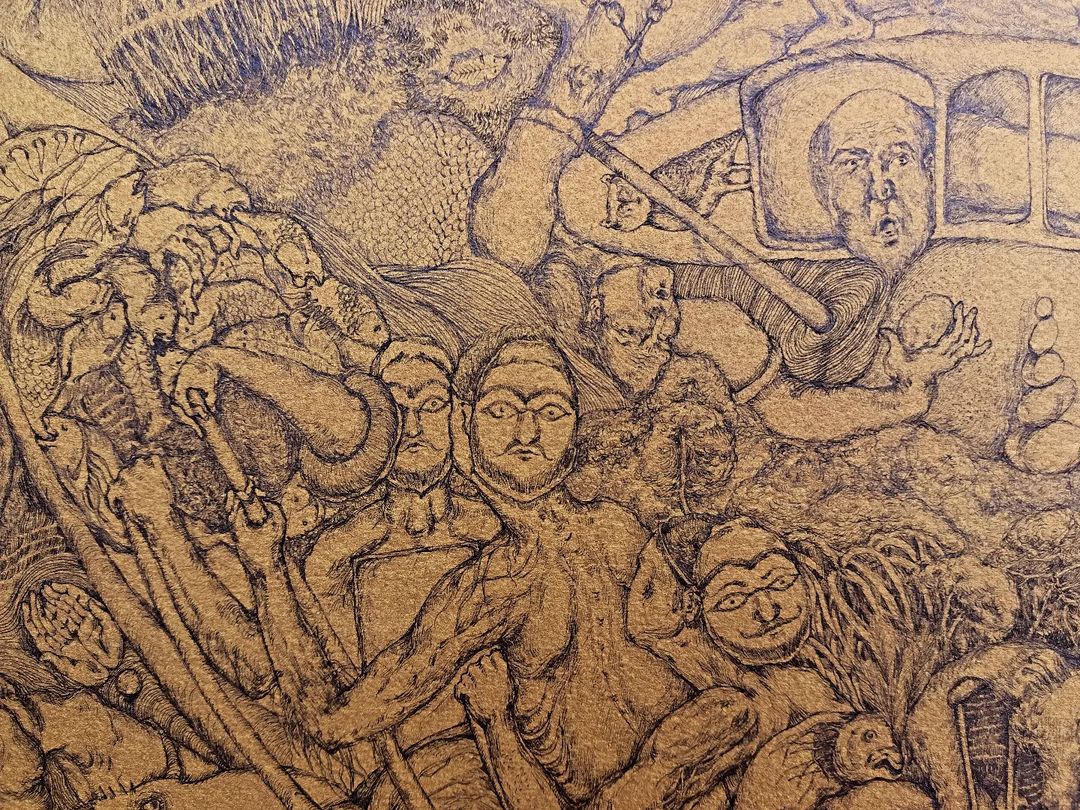

The generational impact of economy, displacement, and extraction, which anchored this edition of Colomboscope, was magnified by the transitions between gallery spaces. In Soma Surovi Jannat’s commissioned work Where Every Leaf Holds a Tale . . . (2023), the artist set up an earthy entrance to Barefoot Gallery with six leaf-shaped, ink-on-paper island landscapes hung horizontally on an ochre-colored wall. These mirrored the real leaves, also displayed in the vitrine, that were collected from the Sundarbans forest of Bangladesh. Jannat’s meticulous ink lines depict images of Mughal rituals, such as unsettling double-faced figures, that recall Bangladeshi workers who were sent by colonizers into forests to collect produce. The workers were unprotected besides from a backward mask meant to deter forest monsters—something colonizers imposed but refused to wear themselves. Jannat’s work recalls this terror through its allusions to an unseen “forest monster” that in fact historically manifested itself as colonial exploitation.

In JDA Perera Gallery, Shiraz Bayjoo’s two commissions also revealed the hidden histories of extraction, often disguised as trade or a higher pursuit of scientific knowledge. Botanical Shrines (2024) takes the shape of domestic-sized altars, honoring native and extinct species abducted from Mauritius in the name of science. The artist’s long-term study at Kew Garden’s archive in London was presented as portraits of plants alongside various forms of currency—pearls, coins, and shells—revealing the colonial legacy of trading history beyond slavery.

Lateb Larenn (The Queens Table) (2024), on the other hand, blesses the transparent skyline with 10 meters of colorful batik fabric. Visible throughout the gallery, the ship-shaped sculptural installation features marble statues of a fictional couple from the French Enlightenment novel Paul et Virginie (1788) erected on top of the Mauritian coastal forest. In the novel, Paul and Virginie, who live with their slaves, fall in love against the backdrop of a romanticized island paradise. Their tragic ending, based on a historical shipwreck, is depicted on the edges of Lateb Larenn as monuments on the island that witness persistent, unfair trading.

At the BMICH Kamatha Open Theatre, Venuri Perera and Eisa Jocson’s work-in-progress performance Magic Maids (2022– ) spotlights the oppression of women’s labor from the Global South. The Sri Lankan and Filipino duo developed the idea, which centers around the history of medicine and witch hunts, during their Basel artist residency. The performance employs gossip, pop music, hysterical breathing, erotic rage, and brooms as bodily extensions, oscillating the audience between the exploitation and glorification of migrant domestic laborers. The artists began by questioning the project’s European funding and ended the performance sweeping the floor in silence, before opening the floor to questions.

These works delve into issues of extraction in relation to colonial critique, but also prompt reconsiderations of the dynamics between the festival’s international funding, its curators, and the local communities. This questioned the potential cultural extraction inherent in the biennial model that is exported to the South, along with global art trends. While the allure of being a “case study” in exchange for relevance in global art discourse is undeniable, can the proliferation of Southern biennials forge a pluralistic art system free of exploitation? Can alternative models be proposed that empower the hosting communities’ artistic agency, even after the departure of international audiences?

In the performance event “Kacha Kacha,” curated by local Tamil artist and poet Imaad Majeed, the dance floor became a safe space for discussions about the post-civil war reality in Sri Lanka suggested by its cross-genre performance lineup at the Government Service Sports Club, Narahenpita. The event’s hybridity of class and language is inclusive of all styles of sounds and dancers, featuring female rappers SajaS, spoken word performer Mishal Mazin, a DJ set by Ka(ra)mi, and bands such as Monsoon Blues & Co. and Orange Mango performing in Tamil, Sinhala and English, was reflective of the changing political dynamic of the host communities.

Discourse about the relationship of global art events and the host communities with the local artists engenders an inter-Asia connectivity that centers on artistic agency and collective trauma. The latter was highlighted in a conversation with artist Abdul Halik Azeez, whose work deals with late capitalism and media monopolies, and shared the urgent concern of ongoing enforced disappearance in some Sri Lankan artists’ works. The subject's sensitivity resonated with political repression during the Cold War and the reparations that followed in many Asian countries, such as Taiwan's continuous efforts to address the "disappeared" victims during its White Terror era, which ended in 1987.

Other members from the Colombo-based collective The Packet debriefed the artistic agency that the festival brought to the community. Some speculate that extended opportunities brought about by a festival’s network can help create a sustainable path for local artists, citing Shironi Joseph, who participated in the 8th Taipei Biennial more than a decade ago, as a rare example of success. Others acknowledged Colomboscope as the only consistent window to the international art community that propelled the formation of the collective. They concluded by emphasizing their agency to accommodate and maintain autonomy through engaging with—or disengaging from—the global network. Unusual in the existing biennial format, the radio commission and touring exhibition of Colomboscope presented a continuous connection for the marginalized art scene that is historically only “activated” through international attention in a limited time frame.

Imagine a forest floor where ontological and epistemological resistances take root, nourished by their own blend of ideas in the soil; it quietly ferments parallel art systems to the existing one, akin to the imagery of diverse trees and ferns coexisting in a forest, each with separate histories that freely collide and influence each other. “Way of the Forest” balanced an exchange by offering an ecological art discourse and gathered the international biennial community at a less-traveled-to location with limited pre-existing coverage. It suggests an ecosystem of art that holds multiple “species” and life cycles, accepting some roots will wither while others sprout, all continuously deepening into the soil even when no one is looking.

What took place was an opportunity to weave honest personal and critical exchange in a city with developing art infrastructure, free from immediate narration tailored to the dominant Western art discourse. As the international peers bonded (being the most “imported” element in the context), they sought to determine a strategy for the South-standing art ecosystem that has become ironically colonialistic. Considering recent economic and political upheaval, fostering a safe space contending with internal conflicts, misremembrance, or silence is essential before exposing the collective trauma to international scrutiny. There must be a deliberate gap between global art trends and local cultural expressions to prevent uninformed categorization and to resist treating crises as a cultural export—especially as biennialization continues to incorporate lesser-known cultures, potentially leading to further resource extraction and exploitation. The forest asks visitors to resist the urge to collect, categorize, and trade, to be no more than a witness of the forest’s growth.

Yu'an Huang lives and works as an independent curator in London, Berlin, and Taipei.