Ideas

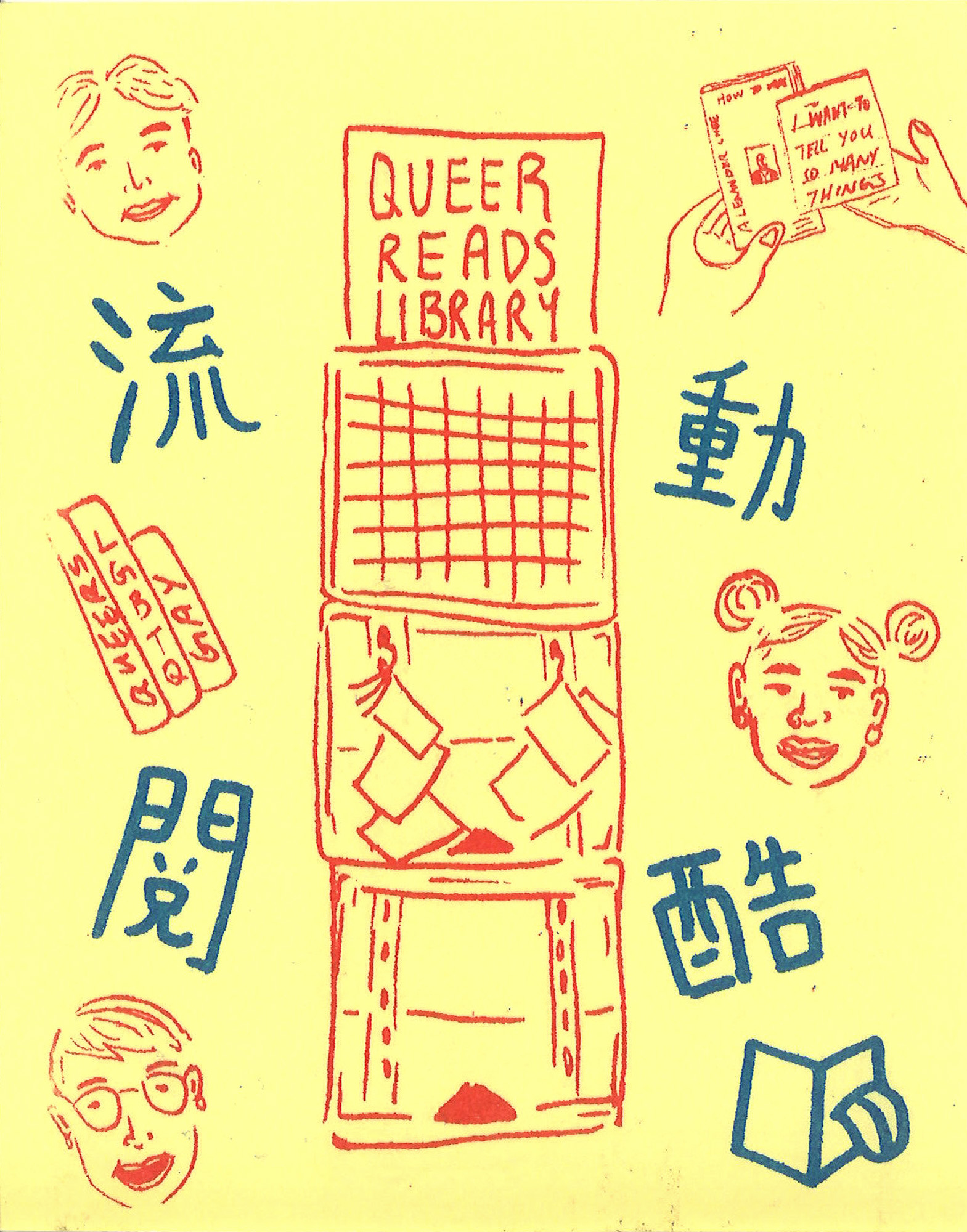

A Visit to the Queer Reads Library

Zines are the embodiment of people taking matters into their own hands. Their early manifestations as fanzines (fan magazines) dedicated to science fiction reveal an active audience, readers who have developed canons further than intended or made their own. Zines then evolved into vehicles of circumvention; subcultures were sowed and fertilized through the circulation of cheaply-made publications via subterranean networks. Among these periphery movements was, and to a great extent still is, queer culture, with many artists and writers publishing their truths and their experiences independent of the mainstream press, with printers at home, in school, or at work.

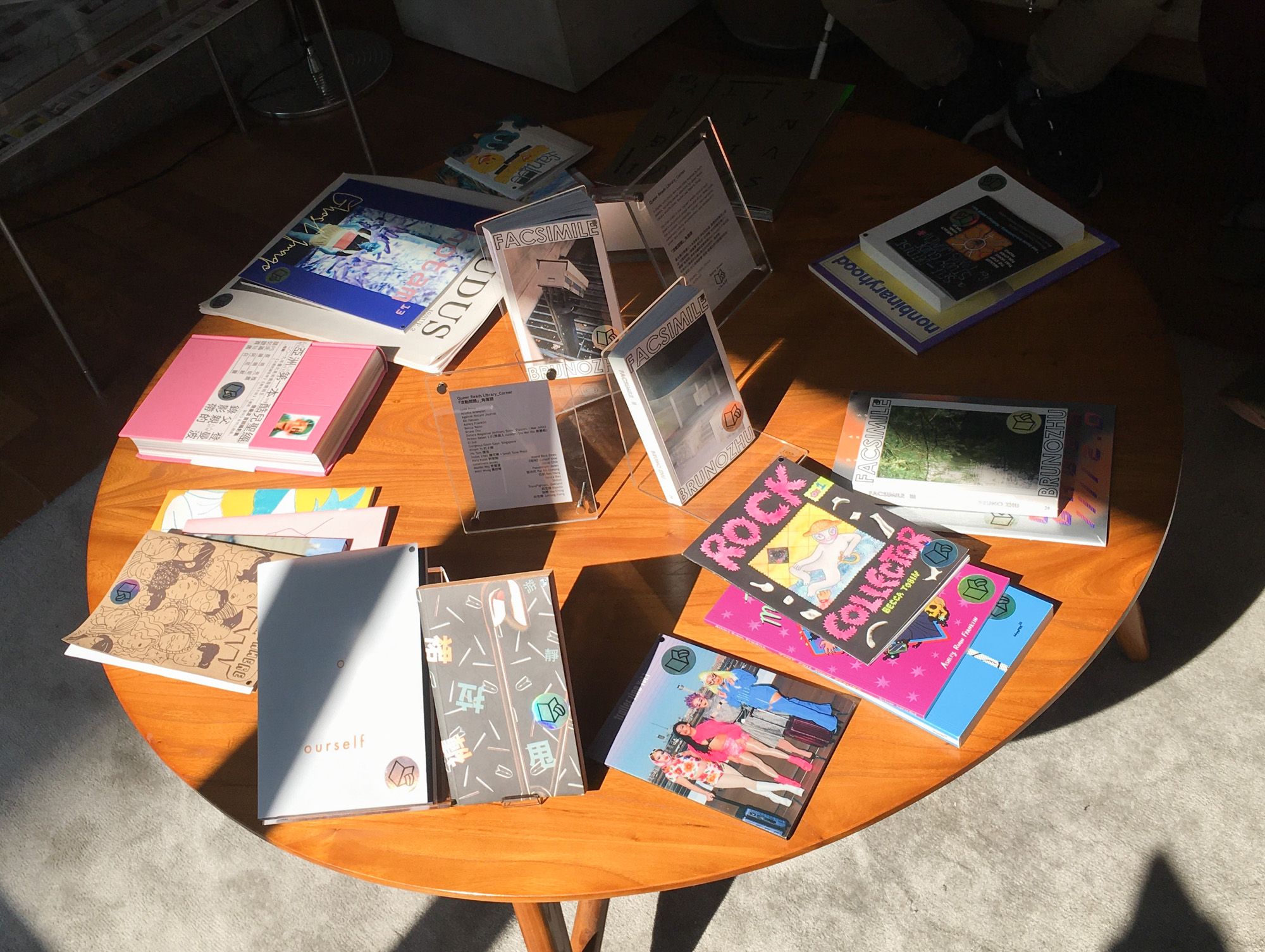

With the very same do-it-yourself spirit, the ephemeral Queer Reads Library (QRL) began in 2018, following the decreased accessibility of queer-themed children’s books from the Hong Kong Public Library. “They’re still in the library, but they cannot be checked out. You would have to register with your personal information in order to read them,” QRL co-founder and artist-publisher Beatrix Pang explained. This “subtle and passive-aggressive restriction” catalyzed Pang, artist-curator Kaitlin Chan, and multimedia artist Rachel Lau to create a library from the queer zines—spanning comics, photography, and literature—they’ve accumulated in their personal collections. Based in Hong Kong and Vancouver, the three artists host physical pop-up libraries internationally, from Taiwan to Shanghai, Osaka, San Francisco, Milan, Buenos Aires, and London, while running an online catalog of the library’s collection.

Since then, QRL has become a firing table for those who want to begin exploring independent queer publications. Their collection has expanded, with donations from numerous university presses and nonprofit organizations, such as Planet Ally and the Transgender Resource Center, and individuals, such as activist-researcher Connie Chan Man-wai and graphic designer-illustrator Po Hung.

In late December 2022, two days before the new year, I visited QRL’s most recent pop-up library at Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun Contemporary, which was on view as part of “Myth Makers—Spectrosynthesis III,” an exhibition on queer mythologies. There, I met Pang and Chan, alongside artist Kary Kwok, whose self-portraits and photographs of queer communities in the 1980s and ’90s populated a vitrine across the reading corner and the pages of his zine titled 106 Men, 69 Women and 10 in Between (1999). With the deep bass of a video artwork reverberating in the background, our conversation covered the ins and outs of library management, the sanitization of queerness, and the role of zines in queer culture.

What is the focus of QRL?

Kaitlin Chan There are a lot of ideas about respectability around LGBTQ+ identity. We want to focus more on people who are doing things that are a little bit more challenging. The work doesn’t need to show a positive or happy image. It could just be people’s fragility, insecurity, wondering, questioning, and introspection.

A lot of the artists we have at QRL work in different fields. They are people in Hong Kong who make publications and want to have an outlet for it, but do not have time to distribute or go to fairs. We also help bring their work internationally. We have been invited to have corners in places like Buenos Aires—so many random things happened to us. People are just nice.

Beatrix Pang We are grateful to everyone who has offered us opportunities. There are a number of overseas collaborators, whom we personally had not known, who gave us a hand and showed interest in more material from Asia and, specifically, Hong Kong. We’re glad that we’re reaching more readers. When we started, we simply wanted to get in touch with people from the LGBTQ+ community in Hong Kong, but what happened after that went much further.

Would you ever open a permanent physical space for the library?

KC I feel as if this paradoxical thing happens: when you have a pop-up collective, people are more likely to go because it’s ephemeral. If you think something will always be there, you probably would not necessarily prioritize or make time for it. People often request us to open a physical space, but how many people would regularly show up to support us if we had a physical space? We don’t want to create that burden of expectation. We’re just doing what we can—literally, physically, sustainably, emotionally, and financially—which is two to four public programs every year. The online catalog is currently updated to around 270 titles, but we have to add all 30 of these new publications on view at “Myth Makers,” so there will be some maintenance and reshuffling. That’s what I like about it: in pop-ups, be visible, do a lot of people-facing and emotional connection work, and then go back into the hole—catalog, organize, do your own thing, and heal from the external interactions.

BP I think the part behind the computer is more like the real librarian, sitting behind the computer and doing all the cataloging.

What is the role of zines in queer culture?

KC There are a lot of really cool queer collectives in Hong Kong who do different kinds of work, such as providing legal services or focusing on the well-being of transgender youth. What QRL focuses on is printed matter, with Beatrix and I being people who happen to love reading and publications, because they’re so deeply important for our own personal becoming and self-history. Each of us could probably list five books that changed our lives.

Books are also a little more financially viable to produce versus TV shows or movies. That’s why a lot of queer people do self-publishing, because that’s how you can get your radical messages out there without having to go through rounds of censorship and editing. Self-publishing allows queer people to not keep cutting, editing, and conforming their identities or their politics in neater, digestible, and friendly ways. You could actually make a publication about literally whatever you want. In Hong Kong, there are certain restrictions now, but the kinds of artistic expressions that we happen to have in the library are very far-reaching.

A lot of people complain, “Why does culture these days feel so sanitized? Why does it feel so homogeneous?” If you want to get culture that is non-homogeneous, you have to look at the independent spaces, whether it’s an underground dance club, a performance art collective, or, in our case, a mobile library. Those are where you can access people’s more unfiltered but still thoughtful, considerate, and true expressions of how they actually want to be, feel, and think about the world, versus something that has to be considered for a broader audience. Who is a “general audience”? Any group of ten people, even in Hong Kong, would be so different.

Kary Kwok A zine is independent and very personal. It’s using low-tech to produce high-tech expression. It can be a political instrument as well, because it can be easily distributed and produced. Zines can leave an historical trail alongside the mass market; it is a subculture for the [culture disseminated by the] magazine.

It is exactly because queer culture has been treated as a subculture for a long time that it found a platform through zines, which are easier to distribute and do not have to undergo the same rounds of censorship as mass media. In zines, ideas can go where they need to be.

KK Exactly. Zines are closer to the bone.

Are there zines you’ve read recently that have occupied a space in your mind? If so, what are they?

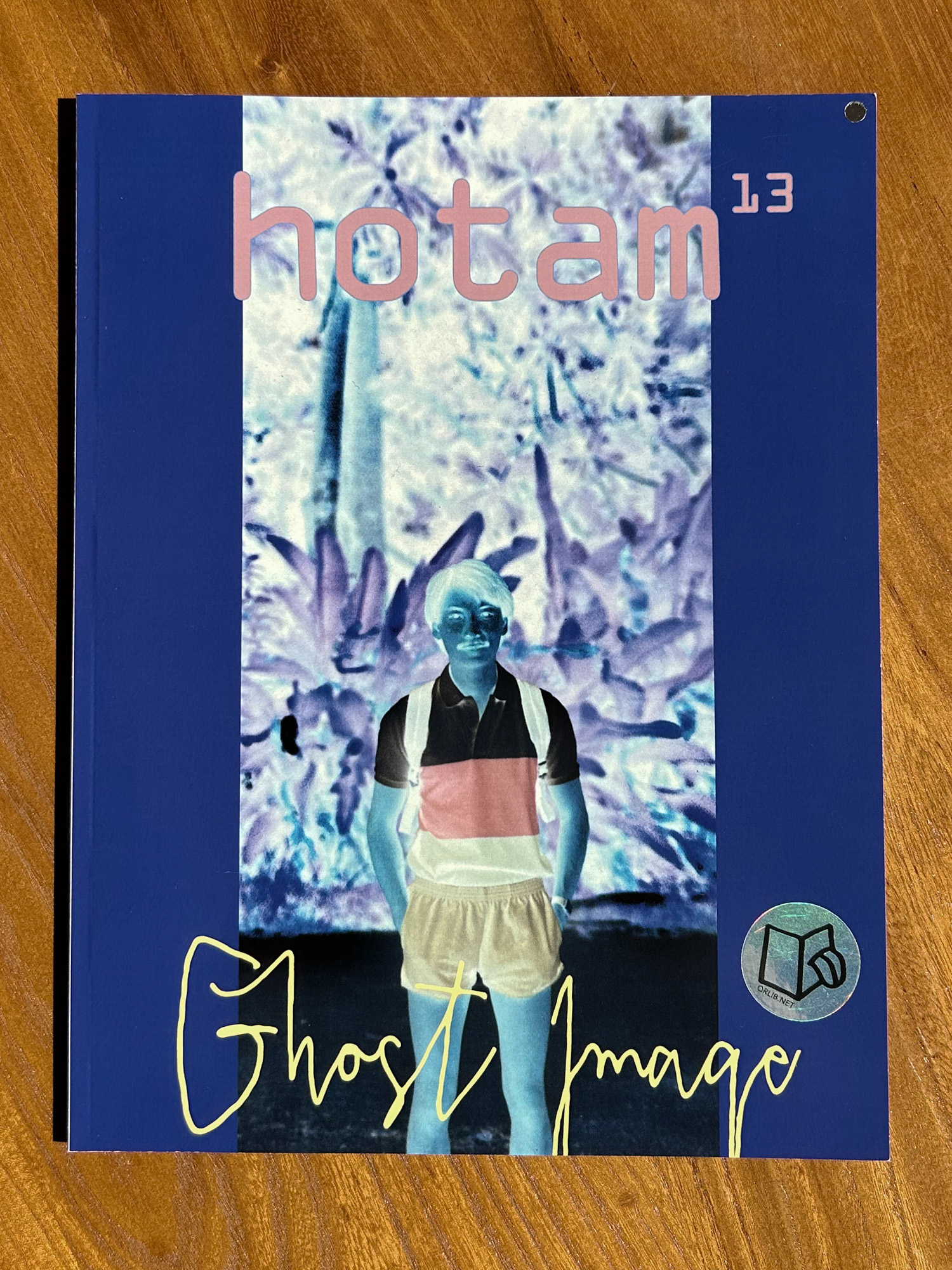

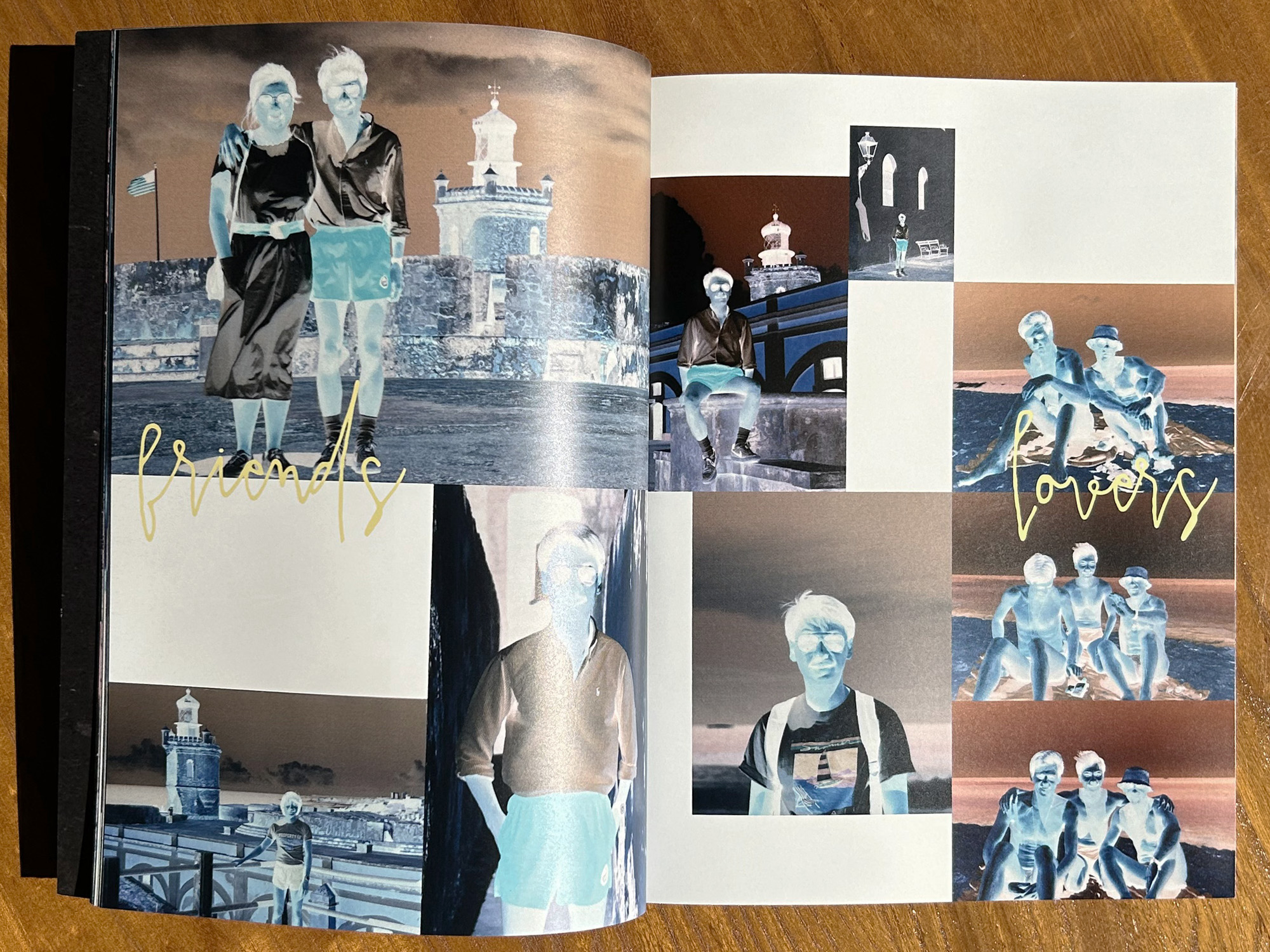

KK Mine is definitely Hotam#13: Ghost Image (2022). I met the artist Ho Tam recently and this zine was so cleverly done. He told me that, because the zine involved a lot of personal photographs requiring getting publication rights, he just printed them in negatives. It created such ghostly but personal images, such beautiful coloring and stunning visuals. He told me how he randomly scribbled text on the photographs. And somehow it worked. So spontaneous, carefree, but concurrently calculated. I think that is the complexity of this publication for me.

KC The way that the negative images look creates such an intense emotional response. They’re not homogeneous even though all the images have been inverted; they’ve been inverted in different ways. And the images follow a certain kind of format that a lot of us are familiar with, whether it’s a portrait of a lover, a self-portrait, or a family vacation photo.

BP I think it’s so nice that Ho showed negative images, because they look like how you would revisit a memory. The images in your brain are not really clear. You barely have the silhouette of someone or something so I think this zine provides a very good treatment of how you present these [memories].

BP I want to talk about this new zine, ACÚDUS ISSUE.2 (2022), by Acudus Aranyian who is from the Indigenous [Paiwan tribe] in Taiwan. Since Covid-19 started, he and his partner moved to New York. We met Acudus in 2019 through Instagram. He wanted to show us his photographic work. It was during the time when Hong Kong started the 2019 movement, so the whole experience of meeting him was so intense, and we got to know each other over a short period of time. Receiving this zine, which he produced during the last two years after he moved to New York, is like continuing our dialogue with him. It’s about his migration to a new place and finding his chosen family, like a photographic diary.

KC We Are Everywhere (2022) is by Gorgeous Glam Gays—which is a great collective name—from Singapore. We’re in Hong Kong and most of what you hear about other countries is unfortunately filtered through international or even local media, which are tightly focused on things that are considered hot-button issues. The way that queerness and LGBTQ+ topics are discussed in the context of Singapore in the news is really stigmatized, focusing on the problem of people having to be in the military and the problem of the illegality of homosexuality, which has only recently been decriminalized.

So when we were curating this pop-up, I really wanted to find some Singaporean perspectives that are independent and on-the-ground from people’s day-to-day experiences. This zine by Gorgeous Glam Gays has a lot of interesting personal essays, illustrations, and texts. It feels really exuberant and badass, a “we don’t censor ourselves, we don’t care what you think” kind of expression of people’s lives. They’re on Gumroad, which is a website where you can independently buy from publishers.

They argue a lot about the challenges in the community, whether it’s biphobia or intracommunity dynamics. It doesn’t feel like they censor themselves, and the fact that they chose to call their collective Gorgeous Glam Gays, that’s the opposite of catering to people who say, “Can you just tone it down a bit?” or “Can you not be so much?” They decided that we are going to be the most and we’re going to be everywhere.

“Zine Review” is a column by ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor Nicole M. Nepomuceno, where she reports on independent print matter.